The Railway Children

I take a lot of flak for liking this film. People find it difficult to believe that the same person who rates ‘Re-Animator’, ‘The Evil Dead’ and ‘Reform School Girls’ among his favourite films, can enjoy a film like this without an ulterior motive. This usually involves Jenny Agutter, though the rapidity with which even total strangers leap to this assumption convinces me that there is a fair amount of fantasy transference going on.

I will admit, make no mistake, that Jenny Agutter is astonishingly pretty in this film (and before anyone accuses me of anything, I should point out that she was 18 when it was made; she used to have terrible problems getting served in the pubs around where they were shooting!). However, this is almost completely irrelevant to the film, in the same way that Nastassja Kinski’s presence in ‘Paris, Texas’ has little to do with why it’s another favourite.

Every frame is carefully calculated and arranged to evoke all the ‘Victorian values’ that Mrs. Thatcher used to witter on about. The characters are so nice and sweet you can feel your teeth rot as you watch this cinematic equivalent of a tin of condensed milk. The film is a totally cynical attempt to manipulate the emotions of the audience. And the worst thing of all is that the bloody thing succeeds – your poor editor, hardened gore-hound that I am, can not watch the end without pretending to fiddle with his contact lenses.

There aren’t many films that have that effect to me. When the mother deer in ‘Bambi’ gets killed, I do reach for my hankie. I also remember going to see ‘E.T’ and not being happy when the little green alien ‘died’ – say what you like about Steven Spielberg, he can twist an audience round his little finger. Of course, when I was younger, I’d start howling at ANYTHING; the first film I can remember going to see that I DIDN’T cry at was ‘Jaws’!

Back to ‘The Railway Children’. I’m sure that the plot is part of the sub-conscious heritage of every British child; a happy, upper middle-class family of mother, father, son, two daughters and several servants, living in Victorian London, have a crisis when father is arrested and charged with working for a foreign power (you can read in subtle social comment here – nowadays, they’d probably claim he bombed a pub somewhere). The loss of their bread-winner means they can no longer afford the massive house, so they go to live in the country, in a nice cottage overlooking a railway line.

The children wave to passing trains, make friends with the station-master (played by Bernard Cribbins), stop a locomotive from crashing into a tree on the line, help rescue an injured schoolboy from a tunnel and generally live the sort of humdrum life typical of country peasants last century. Be grateful we live in modern times, with more interesting things to do in the evening.

Unsurprisingly, there is a Very Happy Ending when Daddy gets released, through the intervention of a passenger on one of the trains the children wave to. Not a dry eye in the house. But not all the novel made it into the screenplay:

“Then Mother undid Peter’s boots. As she took the right one off, something dripped from his foot onto the ground. It was red blood. And when the stocking came off, there were three red wounds in Peter’s foot and ankle where the teeth of the rake had bitten him, and his foot was covered with red smears.”

Ok, Shaun Hutson it ain’t, but clearly Lionel Jeffries didn’t think it was the sort of thing for a U-certificate film (the only U-movie I possess, incidentally!).

Some people have also chosen to read a great deal of sexual symbolism into it. Their reasoning generally involves equating trains going into tunnels with sex – from this it can be deduced that the children’s interest in trains, and especially Peter’s desire to be an engineer, is symbolic of their passage through adolescence. Also, their association of trains with their father may well indicate an incestual relationship, etc, etc. Personally, I think such talk is a load of tripe and that all it proves is that certain people are in need of therapy…

It’s appeal is very difficult to explain – the characters are, without exception, Very Nice, yet I feel no animosity towards them or desire to give them a good kicking, unlike the ‘kids’ in most of Walt Disney’s live-action films! It is also unusual in that it’s dramatic content does not stem from the normal good guys versus bad guys conflict – there are no ‘baddies’ to speak of. This lack of alternative views is perhaps a benefit; with no other characters to identify with, you either associate with the children or stop watching. If we compare it with, say, ‘The Texas Chain-Saw Massacre’ (and I bet it’s the first time those two films have been paired!), in TCM most people end up cheering on Leatherface as he slices and dices hippies, even though this is not what the director intended, because it’s easier than identifying with the whining, flare-wearing victims.

Too much analysis of a film can be counter-productive, perhaps. Maybe we should just write this one off as a personal foible or as a retreat whenever I tire of the sight of psychopathic murderers, demons from Hell and brainless teenagers.

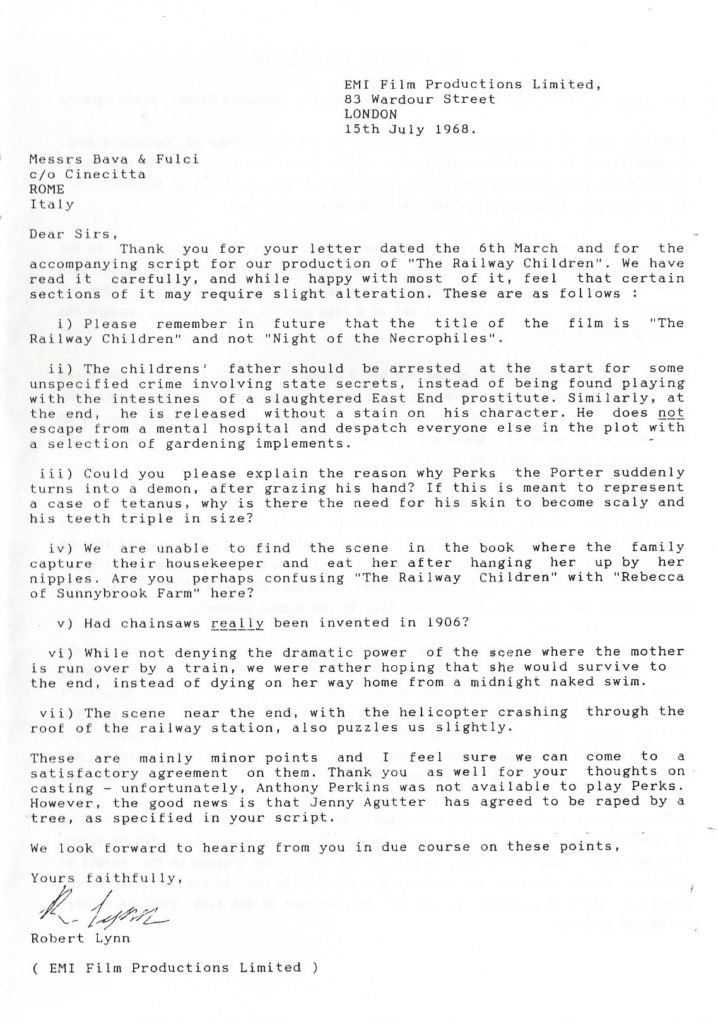

One rarely mentioned fact is that a group of Italians were initially involved in writing the screenplay, before Lionel Jeffries took it over. Below, we have printed a letter from the producer to the people responsible…