Fuzzy Navel, Big Eggs, and Coffee in a Can

“Westerners in Japan spend much of their time being confused”

It’s an alien country, unlike anything you’ve ever seen. The transport systems are impossible to use. The cost of living is unbelievably high. The food is hostile. The natives and their language are incomprehensible. The weather is foul. The customs are unfathomable, and any foreigner there is treated like a quaint and distasteful oddity.

The above facts are pretty much a summary of what I had read and heard about Japan before I left England. I’d prepared for this trip, revised harder than I ever did for my exams. Guidebooks, language courses, The Rough Guide to the World. As I stood waiting for a bus at Narita Airport (which is about an hour’s drive from Tokyo itself), I must admit to being a little worried. Still, here I was, and here I was going to stay for the next two weeks. Having no tangible assets whatsoever, I had put myself in debt for a year to pay for this. It was just something I had to do.

It took me one day to realise that guidebooks on Japan can be compared almost universally to a Texas Longhorn: a point here, a point there, and an awful lot of bull in between….

Not only do they lie a lot, they also miss out things that they should really tell you. For a start, I wasn’t expecting the pavement to be full of bicycles. I stepped out of the hotel at eight in the morning on my first day and suddenly I was in the middle of the Tour De France. They were everywhere, and none of them were doing less than thirty. Only a heroic leap sideways saved me from being sliced laterally into about a dozen pieces. The shriek of mortal terror was purely for show. I found myself in a shop doorway, having my legs hosed down by a tiny Japanese woman in a brown kimono and a baseball cap. I was ready to take this personally until I realised that every doorway in the street had water jetting out of it. They were washing the pavement down before business, just like they did every morning.

While squelching away from this particular revelation I got my first real views of Tokyo from street level. Looking out of the bus window was enough to leave me open-mouthed with wonder, but it’s not the same as standing there and having it all happen around you. Right opposite my hotel was the Korakuen Amusement Park, extending as far up as it did to either side, and containing some of the most sadistic-looking rides I have ever seen. Behind this catalogue of terrors lay the Tokyo Dome, known locally as the Big Egg. They ain’t kidding. It’s a covered baseball stadium and racecourse that makes Wembley Stadium look like a putting green. Using the park’s taller features as a reference point, I got down to the serious business of exploring Suidobashi, the area where I was staying.

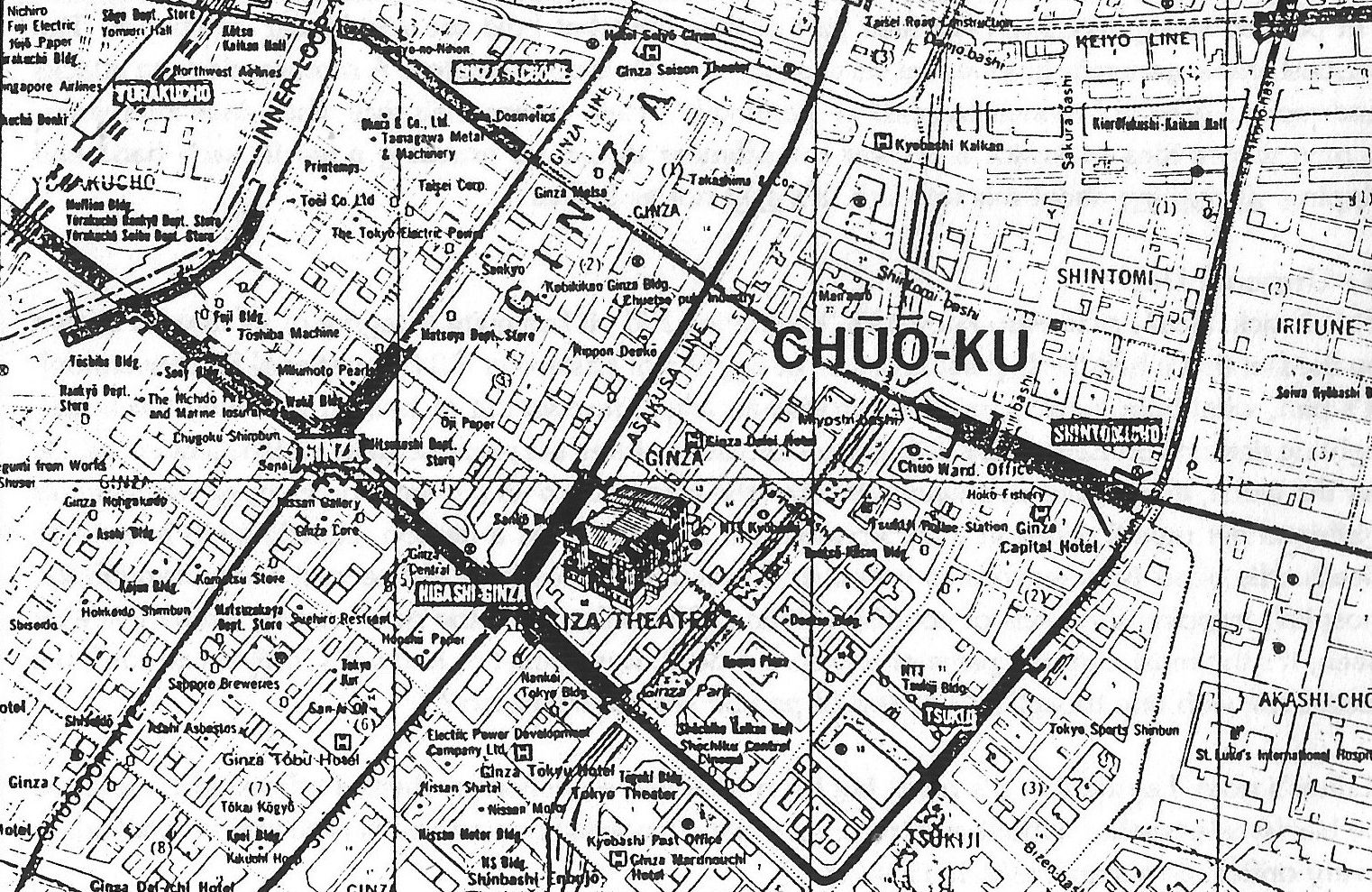

Suidobashi’s shops all sell either books or sporting equipment, and they are taller than they look. Within twenty minutes I was more lost than I have ever been in my life, and the park was completely hidden. It had probably retreated below ground, like the base in Stingray. I had my map, given to me back in London by the people at the Japan Travel Centre, but Tokyo city planners obviously don’t like naming their streets in any way that can be read by the human eye. I began to feel pretty stupid, until I realised that there were groups of Japanese people who looked more lost than I did. By the time I spotted the Korakuen big wheel six hours later I had seen a lot of Tokyo. My feet looked like Bruce Willis’ at the end of Die Hard.

I’d seen a lot, but I’d fallen in love and wanted more. I was getting a kick out of the simple things, like the Japanese writing confronting me wherever I looked, the multicoloured taxis, the dozens of vending machines on every street. If you have a 100 Yen coin in your pocket, you can never run out of cigarettes of canned drinks in Tokyo, regardless of the time. I liked the sound of the language, the faces of the people: the open, interested expressions of the girls, without any hint of the smug self-awareness so typical of the western female. Schoolgirls beam and giggle, old ladies nod and smile, their eyes bright and knowing, and businessmen will happily reveal that they speak better English than you do.

That was the last time I got lost in Japan, because the next day I discovered the Tokyo Underground System. It spreads like a vast spiderweb under the city, connecting everything to everything else. Wherever you look there are station entrances, clearly labelled in English and occasionally Japanese. Once inside you can be anyplace in Tokyo within twenty minutes. What surprised me was the state of the trains themselves: I had never seen tube carriages that were clean, comfortable, and free from litter, graffiti, and drunken skinheads. Some of them had computer displays telling passengers which station they were approaching, which they had just left, what the time was and the latest baseball scores, all in the ever-present Kanji with English translation. How long would that last in Britain without some moron’s Doc Martin going through it?

After I’d gotten the hang of that, I decided to hit Ginza and look for some food, since Aeroflot’s in-flight meals had killed my appetite for the past two days. Ginza is Tokyo’s fashionable shopping district. The department stores there (Depatos) all look like half-a-dozen Harrodses in a stack. They’ve got beer gardens on the roof, food halls in the basement, and everything else in between. I’d read all about this, of course. I’d even seen photos of it. But the reality was enough to turn my brains to jelly. I was walking around like a baleen whale feeds, gob wide open and sucking in experience like krill. Eventually I plucked up enough courage to go into a Sushi bar and try some of the stuff. My first real mistake since arriving. It wasn’t just the bones, the eyeballs, the bits of tentacle with the suckers still attached: the whole thing just tasted vile, kind of a cross between lavender soap and Dettol. I crammed as much of the awful stuff down my throat as I could stomach, trying to convince myself that it is practically impossible for octopus tentacles to reconstitute within the human gut and exact a terrible, Alien inspired revenge, then paid up and staggered off.

That little adventure cost me nigh on twenty quid. Since it’s terribly bad manners to count your change in the shop, I was at least able to get outside before I started crying. Let me state now that this was an isolated incident. As long as I steered clear of raw fish, I got on very well with Japanese food. Japanese drink, too. When drunk hot, Sake tastes like Christmas, and couldn’t get into the brain quicker if it was injected. They have soft drinks there called Pocari Sweat, Post Water (advertised by Bruce Willis, no less) and Fuzzy Navel, and you can get tea and coffee in cans, hot or iced. Noodles are delicious, whichever type you try, and a huge bowl (more than I could eat) can be bought for less than a pound. If you know where to look, you can survive in Tokyo for pretty close to nothing.

I didn’t. Get by for nothing, that is. I’m pretty sure I survived, but changed in ways I wouldn’t have thought possible. I was a lot poorer, for one thing. The hotel I stayed in cost nearly forty quid a night, and that was just room, no food. Two people sharing would pay about thirty each. This is using the coupons issued by the Japan Travel Centre in London: if I hadn’t used these, hotel prices went from fifty-six to nigh on two-hundred quid a night!

I also spent far too much on stuff to bring back. Being a rabid Anime fan, video tapes were an essential purchase. Unfortunately, there is very little sell-through in Japan, and my copies of Dominion 3+4 and Adventure Iczer-3 cost me forty quid a time. All in all, I spent about seven hundred on books I can’t read, videos I can’t watch, and CD’s I can’t listen to (no player). Various conversions cost another hundred when I got back….

Time to go home arrived a lot quicker than I’d have liked. For some reason, I felt more at home in Tokyo than anywhere in England. Maybe it was the feeling of perfect safety prevalent everywhere except the roads and the bicycle-infested pavements: you can ride a Tokyo subway at midnight and be in no danger at all. Even drunk Japanese are totally non-belligerent. They just sing louder and cry a lot. Maybe it was the fact that everything seemed to work. Whatever the reason, it hardly felt any time at all before I was back at Narita airport with a suitcase that exceeded my weight limit by ten kilos and a young Japanese lady telling me that I couldn’t board the plane home because I had not reconfirmed my flight.

This was something else I hadn’t been told about, and it put me at a bit of a loss. Not to mention screaming panic. I had spent all my remaining money on Pachinko the night before, and now I was being told that I would have to stay in the airport for another twenty-four hours….It would have been okay if I could have afforded another night in Tokyo. Thankfully (miraculously!) an English guy turned up at the same time and offered to swap flights with me: he had a reconfirmed ticket but had lost his passport, and would have to return to Tokyo to get it. While I rained burning kisses on his shoes the Japanese lady gave me his ticket home. Fourteen hours in a Russian-built jalopy of an airliner and the grubby lights of Heathrow swung pestilently into view.

When I landed, it was raining. It was cold. The train home was full of morons and the wheels for my suitcase had come adrift somewhere over Moscow. This was supposed to be home. I didn’t like it. I still don’t. The English have got no bloody manners and the shops shut too early. But give me a year to clear the debt and I’ll be back in Tokyo, doing it all over again. I’ve just heard that the Japanese hire about three hundred Brits a year to teach conversational English to pretty little High School girls. I think I may be making some enquiries soon….

P.J. Evans