True Brit

I have fond childhood memories of happy Saturday afternoons spent in a best of three falls contest versus our draught excluder (no mean opponent – it’s tricky to apply arm holds on a long cloth sausage stuffed with kapok). These enthusiastic, albeit somewhat one-sided, battles were inspired by a ferocious devotion to ITV’s coverage of wrestling, and even now, names like Big Daddy, Giant Haystacks and Kent Walton will provoke misty-eyed nostalgia in a large percentage of my age group. Wrestling vanished from our screens in the eighties, a victim of Greg Dyke’s attempt to move ITV upmarket – yeah, I know it sounds implausible in the light of ‘Who Wants to be a Millionaire’ – yet still survives in suburban halls, between Xmas pantomimes and T’Pau concerts. And I’ve become something of a devotee over the past year, even if there’s little chance of seeing anyone even faintly resembling Takako Inoue.

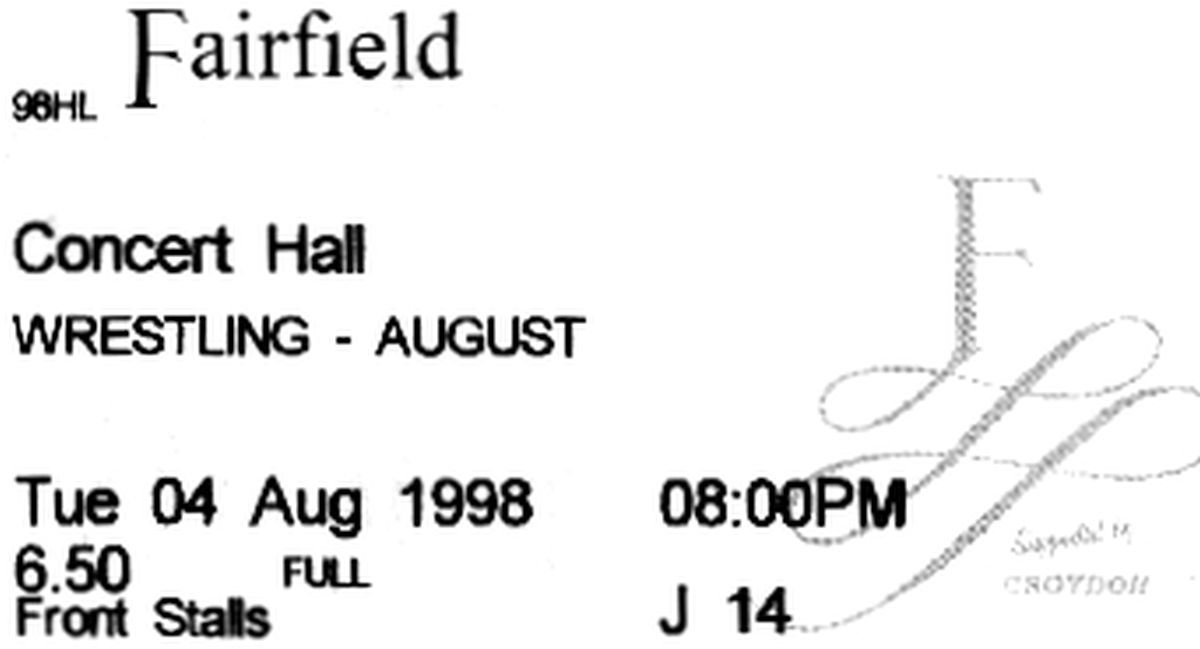

I initially ventured out with trepidation. Some landmarks on the map of childhood memories have stood the test of time (The New Avengers and Kate Bush); others are best consigned to redevelopment (Blake’s 7). Into which camp would wrestling fall? I had little to lose – even the most expensive seat was just £6.50, not bad going for an evening’s live entertainment. And on balance, I was pleasantly surprised. Though not as exciting, excessive, or indeed, cute as the works of JWP and Arsion, I had a fine time, purely from a trashy entertainment perspective.

Crowd numbers are increasing, but a couple of hundred would be typical; almost entirely white working-class, but from kids and teenagers (supporting the villains, with a firm grasp of post-modernism) right up to OAPs. The real hardcore fans sit ringside, and it’s worth joining them. Their exuberant enthusiasm is infectious, occasionally a little too much so – I’ve seen one incensed spectator strip his shirt off and suggest, shall we say, a little amateur bout. However, the eagle-eyed bouncers are always ready to dissuade such individuals, gently but firmly.

In the foyer beforehand, you can buy a selection of ephemera: I just stick to the program, though its worth is questionable – the bouts listed often fail to materialise for one reason or another. However, inside are various bits of news which tend to confirm the current status of wrestling in Britain. Learning that one wrestler suffered a serious knee injury working on a building site proves there are no fortunes being made here.

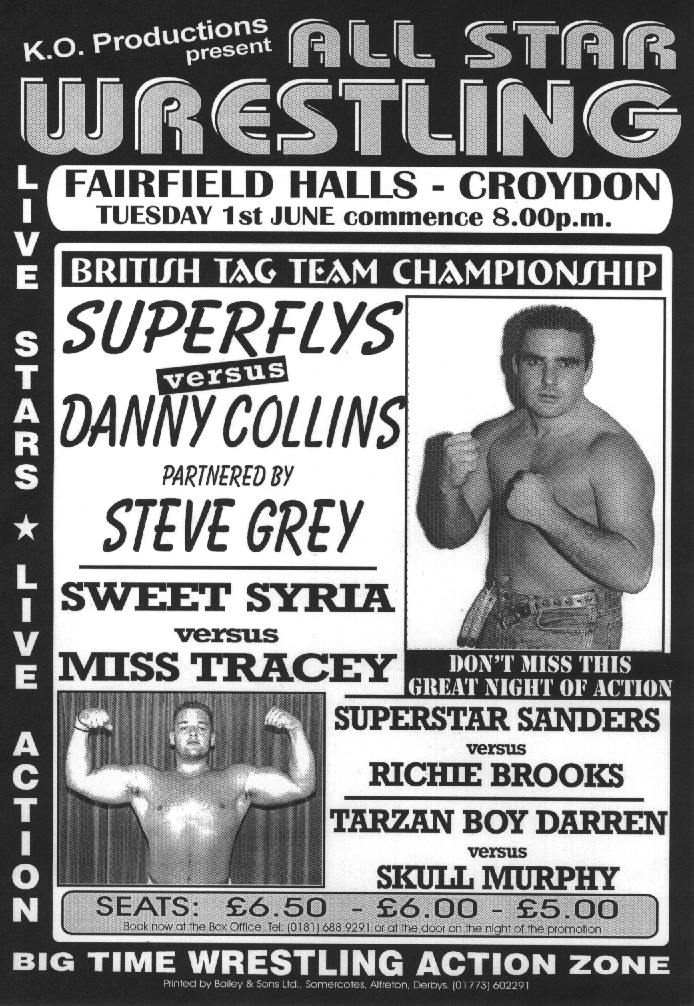

The most striking thing is how small the ring seems. Maybe it’s a mini-version, or memory and the angles of TV were playing tricks on me, but it hardly looks big enough for two people to sit in, never mind pull the sort of stunts performed by Akira Hokuto. For the opening bouts this is perhaps not a problem, as the wrestlers concerned are often of the sort you might politely describe as “highly experienced”. Or put another way, geriatric. I remember the likes of Skull Murphy and Alan Kirby from my childhood (Kirby was the deaf-mute), and so nowadays their combined ages must be near 100. The result is perhaps like watching two uncles struggle drunkenly at a wedding, or an OAP getting mugged, and unsurprisingly relies more on psychology than stunning action. But equally, these veterans know how to work an audience, and this kind of bout is a nice blast of nostalgia to ease you gently back into things.

On the other hand, people like Jody Flash and James Mason (insert obvious cinematic joke) are notably faster and more athletic, with obvious skills which are only a little short of what I’ve seen on tape. Some of the impacts made the ring shudder, and when sound, vision and position work together, the result is impressive and highly convincing.

However, singles bouts seem a little one-dimensional; what generally works the best, in terms of atmosphere and audience reaction, are tag bouts: the two in the ring wrestle, while the other two act as impromptu cheerleaders, whipping up the audience with practiced ease. In this classic, Manichean struggle, the referee stoically argues with one or other face, while his partner is illegally creamed by the bad guys, to the loud disapproval of the crowd. It’s what I remembered it being all about; pantomime, neo-slapstick and larger-than-life characters, a million miles away from Megumi Kudo crashing face-first into barbed wire, but none the less entertaining for it.

With regard to the female variety, it’s less common than I’d like: as mentioned elsewhere, the GLC had a long-standing ban on such bouts, and the women wrestlers largely avoided this area. They do appear occasionally and the refreshing thing is, unlike the tawdry sideshow of the WWF where contests have been decided by the first to lose their evening gown, these bouts are taken just as seriously as the men’s, by promoters and fans. They also provide no less in the way of skill and entertainment – Miss Syria is a personal favourite, in looks and attitude resembling a dark-haired version of Callisto, albeit with a strong Northern accent. I fondly remember one bout, where her opponent was being carried off ‘injured’, and Syria grabbed the mike and said, “I’m really sorry…for kicking your arse!” You just gotta love a good bad girl.

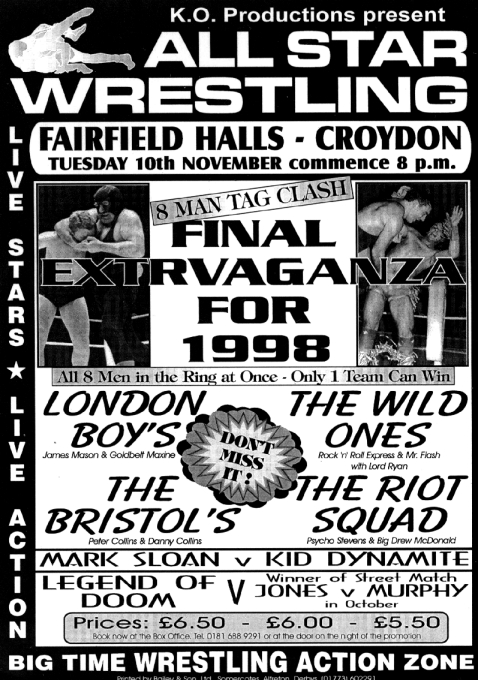

In the middle of the show, there’s a fifteen-minute interval, which seems largely a chance to buy more souvenirs and tickets for the raffle in the second half – some of the prizes in which appear to whatever has been unsold (no opportunity for promotion left unused!), or alternatively, tickets to the following month’s show… Then it’s back to the action once again, culminating in the headline event – perhaps a title fight, grudge match, or gimmick bout, such as an ‘Over the Top Rumble Match’. This starts with two wrestlers in the ring, and another turns up every couple of minutes; the only means of elimination is being put over the top rope. Now, I said the ring seemed small even when there were only two combatants present: with ten wrestlers in there, it is more like a Central Line train at rush-hour; you could almost hear the “Ouch! Mind my foot!”, “Sorry, is that your elbow”, and “Excuse me…EXCUSE ME!“. The MC acts as a commentator, trying to whip the crowd up, with variable results, depending on whether there are any truly convincing heroes in the ring.

Inevitably, victory in the final bout is never unanimous; the loser will claim a rematch because of alleged cheating, interference or whatever. This is done largely as a cliffhanger, to set things up down the line, and build anticipation. It does feel somewhat optimistic to think that the crowd will manage to sustain their interest for a couple of months until the fight gets arranged, but it does at least show an appreciation of the elements required to make a good contest. It’s just that, as in most other areas, the execution is a little shabbier than the Japanese or even the American version. Yet there’s still something quintessentially attractive about the ordinariness of it all.

The appeal is perhaps truly explicable only if you stand on a rainswept Division 3 terrace, laugh at Carry On films, own a Jaguar console, or drive a Skoda, and do so out of choice. You know a more polished commodity is available; you just don’t care. So it is with British pro-wrestling. There’s a huge gulf compared to its overseas cousins, or even the glory days, yet die-hard fans go to Croydon every month. And long may we continue to do so. Now, where did I put that draught excluder?