One Night in Sapporo

Or: “Twenty-six minutes and forty-five seconds of hell”…

Watching Japanese women’s wrestling bouts is certainly enjoyable enough in itself, but to appreciate the true beauty of them, you need also to take on board the bigger picture. For this is not just impromptu brawling: no match stands in isolation, they link with others across time and space in a network of feuds, revenge and drama which would shame many soap operas and in some ways, resembles one directed by Akira Kurosawa. A greater understanding of this hyperviolent jigsaw puzzle can be gained by taking a single bout and trying to unravel some of the threads connected to it. In this case, we’ll take the battle for the WWWA Tag Team Title, in Sapporo on June 18th, 1997.

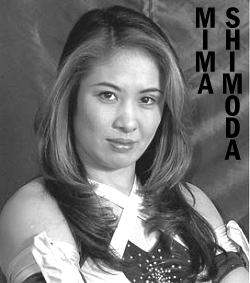

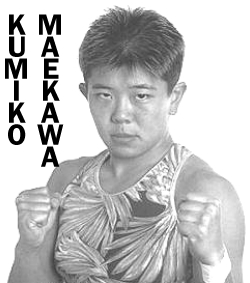

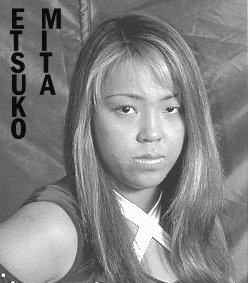

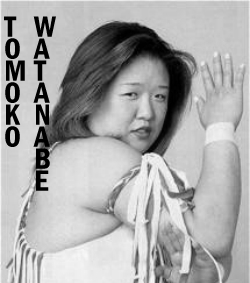

The fight was a rematch: three weeks previously, in Chiba, Tomoko Watanabe and Kumiko Maekawa had retained the title by beating Las Cachorras Orientals, the duo of Mima Shimoda and Etsuko Mita, after Shimoda was disqualified for bringing a foreign object into the ring. Now, this was a contentious decision, in that previously, such restrictions had been largely ignored. Indeed, extraneous objects are often part of wrestlers’ personas: Aja Kong has her can, Bull Nakano her nunchakus, etc. Admittedly, Shimoda brought in one of the steel guard rails which encircle the ring – not so much a foreign object as a totally alien one.

Glossary

Wrestling has a language all its own –here are a few commonly heard terms:

- Blade v. to cut, with the intention of provoking juice. Usually done surreptitiously, by a ringside attendant, under the guise of ‘assistance’.

- Face n. hero, someone regarded as a good person

- Heel n. villain, a wrestler for whom rules are an unnecessary inconvenience

- Juice 1. n. blood. 2. v. to bleed. May be either legit or produced by blading.

- Legit adj. real, true, honest, natural.

- Pop v. to make noise, usually by the crowd.

- Psych n. the backdrop to a fight: the intensity of the combatants and their interaction. Bruce Lee’s fights always had good psych.

- Sell v. to react to moves, in order to show their effect

The second major angle on this fight was Las Cachorras Orientals conversion to heeldom. Their first outing as bad girls had been the previous night in the same arena, when they took on, and destroyed, Manami Toyota and Toshiyo Yamada. Despite being perhaps the federation’s biggest star, Toyota juiced heavily, thanks to Shimoda wielding a pair of scissors on her scalp, and Las Cachorras also became enthusiastic users of chairs – and not from a relaxing, seat-based point of view. [a demonstration by Las Cachorras of the seat’s potential as an offensive weapon might change the minds of anyone who still thinks wrestling is “fake”. Football hooligans have a lot to learn.] Such extreme behaviour was, no doubt, necessary to get them over as heels, but woe betide their poor opponents – and Las Cachorras didn’t even have any particular reason to hate Toyota and Yamada. With Watanabe and Maekawa, because of what had already happened in Chiba, it would be deeply personal.

The scene was thus set for a spectacularly memorable (from the audience’s view) and painfully messy (from the participants’) event, at the Sapporo Nakajima Sports Centre, before an audience estimated at 3,700 – notably more than the previous night. There were several bouts as warm-up, including a horrible mismatch: Kyoko Inoue and Aja Kong, combined weight: 432 pounds, against Rie Tamada and Yumi Fukawa, combined weight: 255. It didn’t last long. The crowd also saw a severely taped- and gauzed-up Toyota return to the ring, only to juice some more. Then, it was time for the gladiators to enter.

At thirteen stone, Tomoko Watanabe is the Samo Hung of women’s wrestling; solidly built, yet her speed and agility belies her size. In contrast, Kumiko Maekawa is a lean, mean, fighting machine with a crew cut, and the lightest of the four fighters. Compared to these two, Las Cachorras are über-babes: Etsuko Mita is one of the tallest in the business, 5’8″ being well above average height; Mima Shimoda is the prettiest of the lot, but her smile conceals a streak of vindictiveness, now bursting into full bloom.

The bell rings, and Maekawa faces off against Shimoda, kicking away at each other: this is perhaps Maekawa’s area of greatest strength, so Shimoda brings in Mita. She pile-drives Maekawa instead, and has the better of the earlier exchanges, until Watanabe in turn comes in to help her partner. Mita takes badly to this, and hits Watanabe with the first chair of the bout. Time for everyone to meander through the auditorium - plenty seat-shaped ammo there – and by the time they return, Watanabe is juicing, and miffed. She tries to bring a chair of her own into the ring; when the referee blocks this, Shimoda kindly gives Watanabe hers – yes, predictably, across the head. Maekawa’s peroxide hair is already looking closer to strawberry blonde as the blood seeps through. Mita attempts to deliver seat-flavoured justice to Watanabe; she ducks, and Mita biffs her partner instead. A second attempt is more successful, Mita hitting the target as Watanabe prepares to leap off the top rope. However, Watanabe has the last laugh, pinning Shimoda in just over nine minutes.

Phase II sees Maekawa largely on the receiving end. First, Shimoda holds her, allowing Mita free access to her head – open that scalp wound! The bottom rope is slowly loosening, and eventually lies on the ground. Shimoda unties the turnbuckle padding in one corner and tries that as a weapon: brief tests conclusively prove it’s less effective than, oh, kicking Maekawa repeatedly in the head. Maekawa, in the de-padded corner, slumps to the canvas. Given the lack of a bottom rope, this is a bad move: she topples gracefully back, out of the ring, head first onto the floor.

The mats, usually placed round the ring to cushion impacts, are missing for some reason. Maekawa’s skull thus meets solid, bare floor, and she is not happy. Shimoda somersaults off the top rope, down ten feet onto both her opponents – neither look happy – then joins her partner, who is piling chairs up in the middle of the ring, perhaps hoping to save time by dismantling the arena while the fight is still going on. Naturally, this also provides a large pile of scrap to which Maekawa’s back is introduced, and for good measure, a guard rail is thrown on top of her. A hugely pissed-off Maekawa gets on top of Shimoda, and starts raining blows down on her head – referee Bob Yazawa can’t get her to stop, so has to disqualify her and award the fall to Shimoda, who becomes the third member of the match to become an involuntary blood donor, while Maekawa attacks the ref in a frenzy. It took nine minutes, fourteen seconds for the equaliser, setting things up perfectly for the final session.

Maekawa is still furious, and Shimoda is selling her ‘concussion’ big-time, looking as stunned as a Norwegian Blue. Mita saves her with chair-fu, then introduces Maekawa to the guard rails again, before taking her off into the darkness. A rapidly recovering Shimoda piledrives Watanabe into a table, and Mita and Maekawa reappear, brawling on the front row of the balcony while Shimoda gouges Watanabe with scissors – as if there wasn’t enough blood already. Mita dumps Maekawa off the balcony, and she drops to the concrete below, where Mita then tries to hang her, using the now completely detached bottom rope. Watanabe pins Shimoda but the ref is dealing with the Maekawa/ Mita war, and by the time he returns, Shimoda is free – a chair announces Mita’s return, and prevents any immediate re-occurrence. By now, the crowd are popping like mad for each near-fall, regardless of who’s on top: in the end, it’s Mita who hits a Death Valley Bomb on Maekawa for the decider, to give Las Cachorras the title, though Watanabe still wanted to fight on.

In the post-match interviews, Shimoda looked like a poster child for the local women’s refuge – “Just Say No to Domestic Violence” – even if, beneath the caked blood and the bruises, you could still sense a wolfish delight in the carnage and the adrenalin buzz. Mita, on the other hand, was almost unscathed, like the accident victim who miraculously walks free when all around her are maimed. Her day for bloodshed would come. Notably, there were no post-match interviews with Maekawa and Watanabe. Just shots of the ambulance taking them away.

This was one fight on one night; a title bout, sure, yet rated by Mike Lorefice, an authority on such matters, as only worth four stars out of five. Nor was it even especially raw or bloody: in particular, three months later, Las Cachorras would appear in a cage match – a bout where the ring is surrounded by a twelve-foot high steel fence, and victory goes to whichever team escapes first – which would make tonight’s encounter look like a garden party.

However, it isn’t just thrilling and engrossing on a visceral level. Although the agility and skill on view can certainly not be denied, the sheer complexity, not just of the mayhem, but the set-up which surrounds it, also deserves much respect. This background effort is not generally apparent to a casual viewer: the more I watch, the more I am able to delight in the hidden labour which goes into planning, scheduling and promoting the best bouts.

But if watching the fight proves one thing, it’s probably this: anyone who denies that violence can possess a terrible beauty, has clearly not met Mima Shimoda and Etsuko Mita…

[2021 update: Thanks to the wonders of YouTube, you can now see the match]