The Incredibly Bad Book Show

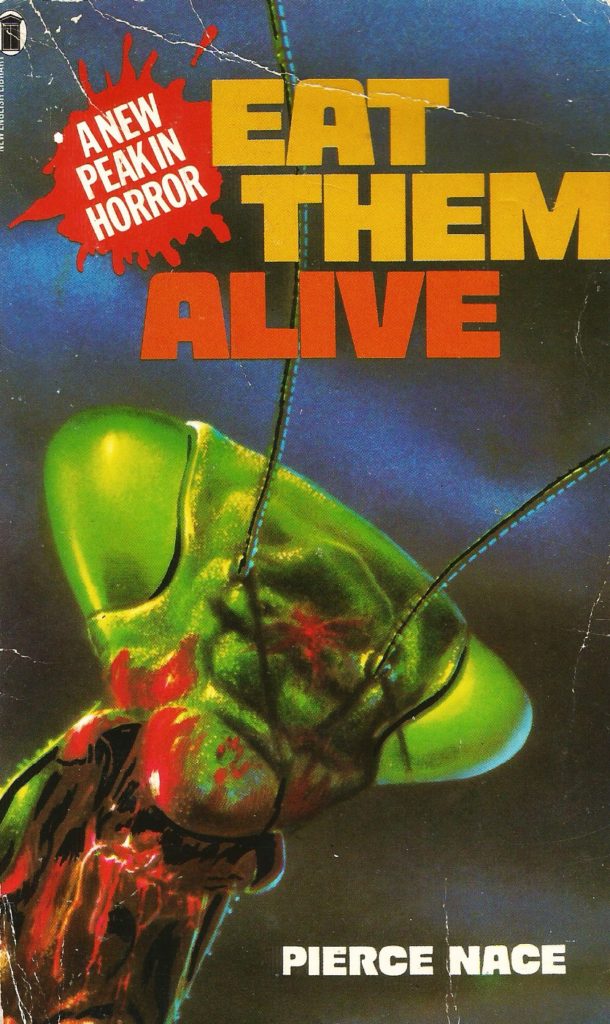

‘Eat Them Alive’, by Pierce Nace, NEL, 75p (in 1977), pp 158.

Described on the cover as “a new peak in horror”, this book marks probably the lowest depths the great New English Library, publishers of James Herbert and Stephen King, have ever sunk to. In a genre not exactly noted for humour, this book succeeded in making me giggle hysterically on the train into work providing my fellow commuters with the edifying sight of a sober suited gent biting his hand while reading a book whose cover depicted a blood-stained insect chewing a gobbet of flesh.

Let’s be honest – it is no exaggeration to say I was capable of producing more coherent, better written stories when I was eleven, and I wasn’t an especially gifted essayist. The whole book, presumably written under a pseudonym, is the literary equivalent of a ‘Best of Italian Cannibal movies’ tape put together by the Monty Python team while out of their collective heads on amphetamines. However, enough talk; let’s continue with a prize example, in both style and content:

“I wonder what it’s like to watch a beast eating a part of your body while you’re helpless to prevent the gruesome snack that you’re arm is providing. Well, he thought on, I’m right-handed. If Slayer bites off one arm, I’ll still have my best one.”

Slayer, in case you were wondering, is a giant preying mantis. An earthquake opens up gigantic cracks in the earth on the South American island where Dyke, the main character (‘hero’ is not the word, as you’ll see) lives and these monsters crawl out and chew their way through the entire population. Inverse Square Law, get outta here:

“What were those giant creatures that were crawling out of the cracks in the earth? Were they animals of some strange kind? Were they outsized snakes…? But no. Snakes had no flailing legs, no bulging bellies, no shapes like – whatever those things were. They were insects!”

Fortunately, Dyke was out in his boat when the mantises appeared and was thus safe to watch the spectacle. As early as page 9, we start to suspect he may be a couple of sandwiches short of a picnic – “But now I’ve got something to live for, because I LOVE watching a man being eaten by a monster! Maybe it’s a substitute for my lost virility, I don’t know”.

The same page also sees an octogenarian ripped apart, with a flagrant disregard for the rules of English; one sentence contains the word ‘and’ no less than FIVE times. We are then treated to a flash-back, to explain why he’s lost his virility. This is not his only problem: “No man’s mind could forget the viciousness Dyke had suffered, especially when it left ever-present headaches and impaired eyesight in it’s wake”.

This all came about when Dyke was young; he and his three criminal associates in the South of the States decided to try a big job – as can be judged for the following passage, Mr Nace has a keen, sympathetic ear for racial minorities and their patois:

“Pete Stuart was the really mean one. He was from an eastern ghetto somewhere, white enough to pass but gouging out the eyes of any man – or woman – who called him anything but black… His best leisure activity was chopping small animals to bits or maiming children… It was Pete who jolted the lot of them out of their lethargies one morning when he said ‘I don’t know about you damn whiteys. But I’m sick in’ tired of penny-ante stuff. I’m takin’ me out to get me some bread that’ll buy somethin’ big. You damn whiteys can come along or not, suit yourselves'”

[The dialogue is reproduced word for word].

They go on to dismember another OAP (senior citizens have yet to catch up with teenagers as favourite targets, despite Nace’s best efforts), but after making their getaway, Dyke tries to sneak off with all the swag. This action is not taken kindly by his partners in crime, who take their revenge by castrating him. Here, Pierce shows a mealy-mouth approach which is a little surprising; given his enthusiasm for sentences like: “Slayer clawed at the abdominal cavity, tearing it apart, wrenching the intestines and stomach from their hold on the man, chewing down the coils of intestines as if they were the greatest delicacy he had ever tasted”.

It’s odd to hear him using phrases like “manhood” and “private parts”. Dyke is left for dead, but is rescued and nursed back to health, or at least, NEAR health as we hear in this exchange between him and his doctor (all … are Nace’s, for once!):

“Will I be – all right? I mean, except for…”

“Yes, except for that. And…”

“And what?”

“You will not have twenty-twenty vision again”

Back in the present day, Dyke captures a mantis which he plans to use to extract revenge against his torturers who, handily, have also decided to settle in South America. He names the insect Slayer and tries to train it; before he has done so, the creature escapes – the descriptions of Slayer as lightning fast are slightly devalued by the discovery that it’s prepared to hang round while Dyke delivers a soliloquy (Nace is unable to cope with his characters THINKING anything, probably because he’s incapable of it himself, so they all speak their thoughts aloud):

“God, he’s out! He’ll kill this scum and me too! Nobody will have a chance against him. He’ll kill everything in this whole jungle, animals and men and women and kids! Nobody’ll be safe from him!”

Such respect for human life is a little inconsistent – “this scum” refers to a native he found in his hut, and who was about to be offered to Slayer as a snack.

Slayer is recaptured and eventually taught NOT to eat Dyke, who smears himself with a foul smelling stuff (that also kills armadillos when a pint is forced down their throat). He’s then off, accompanied by Slayer, pausing only for a snack at a local village, or to be more accurate, OF a native village – he takes all the inhabitants across to the island (more sympathetic ethnic dialogue: “Man come by yesterday, say green things there. Big, fierce. Scared to go.”); the insectoid equivalent of home delivered pizzas perhaps. These sights (entrails, glistening, blood, torrents, fill in the blanks yourself) turn Dyke on, because “for a man who could never make love to a woman, who had put females from his mind years ago, the sight of one being denuded and dined upon should excite and delight him immeasurably”. Er, yes.

Having acquired a few more mantises, he heads off to get revenge on his torturers. The first one he assaults is Pete, who mysteriously no longer speaks like Eddie Murphy doing an impression of a Black & White Minstrel. At first, he doesn’t recognise Dyke :

“Remember me now, Pete? Or shall I take off my pants and let my castration jog your memory?”

Eventually, he does and, along with the rest of his family, is turned into a “muggy slush”. The other three follow in rapid succession, with THEIR families – having spent 107 pages building up to this, it’s a sudden collapse to 149 all out. leaving Dyke burbling to himself as ever: “Am I insane?… Yes, I could be. But if I am, I’m a happy mental case.”

In a sudden turn-around almost up there with “and it was all a dream”, one of the murdered men turns out to have a brother, who gets his own mantises using a “suit of armour they couldn’t bite through” and shoots Dyke; Slayer eats them both and is killed by the poison in Dyke’s ointment, which suddenly stops repelling the insect.

The End. Of course, I may be entirely misjudging it – the book may be a subtle comment on totalitarianism, with Dyke representing a tinpot dictator and Slayer the secret police. I doubt it somehow – the overall impression is that even the raison d’etre, the messy bits, were constructed by pulling words at random from Shaun Hutson books and rearranging them having carefully removed all traces of literary skill. A lot of trees died in vain for this one – perhaps we could get the same people who made ‘Slugs’ to film it?