Cinema

From our Western viewpoint, it is often difficult to appreciate the beauties of oriental cinema, brought up as we are on the conventions and standards of American, and to a lesser extent European, film-making. Yet it is perhaps here that we can best learn to appreciate their culture – non-animated TV series are restricted almost completely to martial arts series, such as ‘Monkey’ (which while highly enjoyable, can not truly be said to give us much of a deep or meaningful insight into their psyche) and literature written in Chinese or Japanese is notoriously difficult to translate; how do you go about converting a phrase into English where each individual ‘letter’ has a meaning?

Admittedly, ‘films’ and ‘the Far East’ to most people mean Bruce Lee and his descendants, Bruces Lea, Li, Ley and Lu. This is like saying all Western films have Streep and Hoffman in them. Mercifully, not the case though if you look at a film like Ridley Scott’s ‘Black Rain’ to see that despite it being a

damn good thriller and a far worthier sequel to ‘Lethal Weapon’, say, than ‘Lethal Weapon 2’ was, it’s Japanese setting could just as easily have been any American city, save for a couple of mutterings about ‘honour’ and a decapitation by Samurai sword.

Undoubtedly the most internationally acclaimed Japanese director is Akira Kurosawa, possessor of many awards now including a Special Achievement Oscar for his contribution to the world of cinema. Despite having taken five years per film since 1965, the man’s influence has been considerable – ‘The Magnificent Seven’ was a remake of his ‘Seven Samurai’, ‘For a Fistful of Dollars’ bears certain resemblances to the 1961 film, ‘Yojimbo’ and even George Lucas has been influenced, R2-D2 and C3P0 being based on characters from ‘The Hidden Fortress’, made 20 years earlier. As an introduction to his films, you could do no better than ‘Ran’, his 1980 version of Shakespeare’s ‘King Lear’ (he borrows things too – ‘Throne of Blood’ was ‘Macbeth’ in a feudal Japanese setting). An elderly Samurai lord devolves his powers onto his three sons in order to effect a smooth transition when he dies. The youngest son disagrees with this and is sent into exile for his pains. The eldest son then argues with his father after one of the former’s soldiers is killed by the latter and the father is driven out. The second son proves no more hospitable and the ex-lord is driven out, insane, to wander in the wilderness accompanied only by his faithful adviser and a Fool. Meanwhile, all the sons struggle for power, destroying everything that their father had built up.

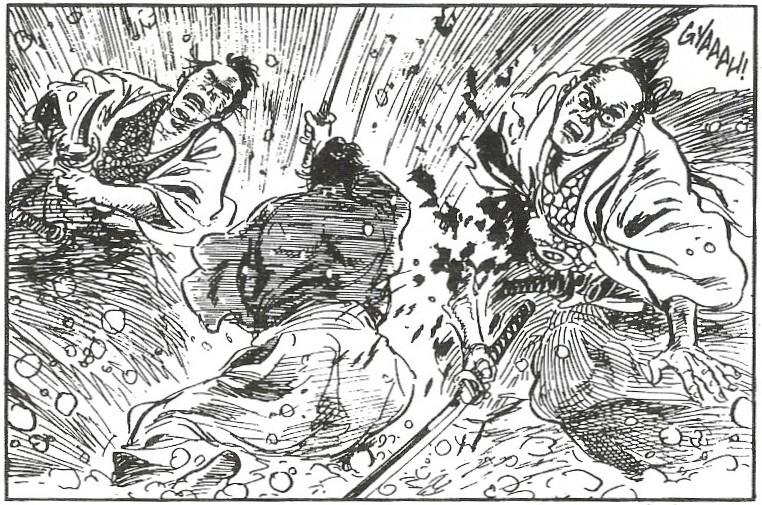

It’s more entertaining than it sounds. It reminded me, surprisingly, of some sort of weird Japanese soap opera – if ‘Dangerous Liasons’ was ‘Dynasty’ in pre-revolutionary France, then ‘Ran’ is something similar in medieval Japan. All the characters spend their time conniving and plotting, the costumes are way out in left field and it bears little or no relation to ‘reality’ (= E.Dulwich in 1990). Despite being comfortably over the two-hour mark, there are few dull moments. There are some impressive battle scenes, or at least post-battle scenes – for the real thing, you should watch ‘Kagemusha’, which makes ‘Henry V’ look like a fight in a school play-ground. There is a healthy interest in death, especially of the violent sort, which runs throughout a great percentage of Japanese films, which in this film climaxes with one arterial fountain of (on-screen) blood following an (off-screen) beheading. In Kurosawa’s case, this may be related to an incident which took place in 1923 – when he was 13, his brother forced him to examine the aftermath of the Tokyo earthquake of that year. He asked his brother that evening why he’d done this and was told “If you shut your eyes to a frightening sight, you will end up being frightened. If you look at everything straight on, there is nothing to be afraid of”.

This confrontational approach runs throughout Japanese film-making, resulting in an uncompromising and occasionally uncomfortable ( to Western eyes ) world view. Only the Japanese would consider making a film, ‘Ai No Corrida’, based on the true story of a geisha who cuts off her lover’s penis with a knife after a torrid session of love-making and wandered around with it until she was arrested. More remarkably still, she is the heroine.

Even in mainstream films like ‘The Ballad of Narayama’, death is accepted as a fact of life(?), rather than something taboo, as it still often is here. This contrast resulted in ‘Ai No Corrida’ being refused a certificate in this country and another film which ran into problems here was ‘Shogun Assassin’, often regarded as being perhaps the ‘best’ film to suffer under the ‘video nasty’ clampdown. Perhaps because of this artistic appreciation, it is still occasionally seen, even in reputable video shops – another, more plausible, explanation is confusion with any of the hundreds of similarly titled films. It was made by editing together a series of films, removing most of the plot, leaving only the startlingly sanguinal fight sequences, but even these have power and grace. No victim of Freddy Krueger uses his last words to praise the skilful way his wind-pipe has been sliced open!

A review of Japanese cinema isn’t complete without mentioning the monster movies produced by Toho Studies. Although Godzilla is the best known of these, there were a supporting cast of characters, such as Megalon, Mothra and Gargon, who did basically the same thing i.e. trample Tokyo. Channel 4 are at the time of writing showing a season of these, late night on Fridays. Not to be missed, especially for fans of rubber, though personally I found that after a while, seeing teeming cities crushed underfoot by very bad effects and hearing Japanese speaking with Californian accents begins to lose it’s novelty.