Wrestlemania 26: An eye-witness review

If, as previously argued, wrestling has the potential to be art, then Wrestlemania is its Hermitage, Louvre and Guggenheim all rolled into one, except far more popular. The 26th incarnation of this wrestling extravaganza, with eleven matches in total, was held in Phoenix over the weekend. To give you some idea of the scale, it drew more people to the University of Phoenix stadium (confusingly, located in Glendale, not Phoenix), than when the Superbowl was held there in 2008, and setting a gate receipt record of $5.8m.

Along with 72,217 other people, Chris and I were in attendance, and after the jump, you’ll find our eye-witness review of the sports entertainment spectacle. But if you want to save time, we agreed that next year we’ll watch it on pay-per-view…

It was my first time inside UoP Stadium. From the outside it’s not exactly spectacular – it looks like someone dumped a white spare-tyre right in the middle of the desert. But when you go inside, you appreciate you just how large a venue it actually is. I’ve been in bigger venues – the Rose Bowl in Pasadena holds over 90,000, the Berlin Olympic Stadium capacity was 110,000 when I visited it in the 1980’s – but those are both outdoor venue. Seeing 70,000 people with a roof over their head is quite something else [the roof is retractable, and they opened and closed it several times during the course of the event, for no readily apparent reason. Not so impressive: having to pay $20 to park at the stadium. Glendale has little public transport to speak of, so there was basically no alternative. When you are paying an average of eighty bucks for a seat, that should include a parking spot.

The main issue – and why we won’t be back – was the seats. “Did you bring the binoculars?” said Chris when we saw where we were sitting. We had actually paid more than average, but were still amazingly-far from the action. The pic headlining the article was taken from our seats – it may take you quite some time to find the ring. The screens around it did show the matches in progress, but if you’re just going to watch the event on television, that does somewhat dilute the point, no? Having been attending local wrestling shows for more than a decade, both here and in London, there’s an inverse-square law in effect, with regard to the impact the matches have – it drops off sharply with increasing distance. Pro-wrestling, like striptease, needs to be experienced close-up for the best results.

That said, the rest of the spectacle on view was undeniably impressive, with the arena turned into a massive cathedral of wrestling, filled with pyrotechnics, lights and really, really big video screens. The seats were also more comfortable than we expected – no bad thing, as we were in them for nearer five hours than four – and there was plenty of space just outside the section, if you wanted to chill, and get a drink or a souvenir. Though you had to be pretty quick with the latter: WWE seemed to have underestimated the demand for merchandise, and the T-shirts for the event were gone before about half-time. Though, I suppose, better to sell out than be left with 10,000 unused, and of limited appeal, after the show.

However, the main purpose is, was and always will be, the matches. Wrestlemania is where all the storylines which have been set up in the preceding months come to a conclusion – it’s like the series finale of all your most-loved shows, rolled into one night. At least, that’s the theory: particularly in a dull first half, there was very little to generate significant excitement in the crowd, either with the quality of the matches, or their emotional impact. Our major interest was seeing people we’ve worked with at the local events, like Mike Knox and ring-announcer Justin Roberts. Otherwise… Well, the opening match screened saw the tag title defended in less than four minutes: one wonders what the point of that contest was.

There was a brief uptick in the middle, when fan-adored Rey Mysterio beat straight-edge heel CM Punk. That had actually had a decent back-story, Punk having reduced Mysterio’s daughter to (disturbingly genuine-looking) tears during her birthday celebration some weeks previously, understandably incurring the wrath of her father. Both men are among the most gifted technical wrestlers in the business, and the heat they generated in the crowd reaction certainly surpassed anything we had seen previously. However, once more, the actual match was over in six and a half minutes: it deserved far more, and felt more like a warm-up contest than anything putting a full-stop on the feud between the two men.

And then there was Bret Hart vs. Vince McMahon, chairman of the WWE. This one had its origins in 1997: Hart told McMahon he would leave the WWE for another company, but they agreed Hart would go out as champion. However, McMahon changed the script, unknown to Hart, and Hart lost the title in what became known as the “Montreal screw-job”. After the match, Hart spat in McMahon’s face, and the two were enemies – genuinely- for more than a decade. However, this year, Hart was brought back as a guest host, and from there developed the storyline which led to him facing McMahon at Wrestlemania.

The chairman brought out Hart’s family, announcing he’d bought their loyalty, but Hart said he knew that – his family had taken the cash with no intention of selling out. The entire family then proceeded to beat up McMahon. For eleven minutes. Now, Hart had a stroke in 2002, and has hardly wrestled since (there were apparently insurance issues, with Lloyds having paid out ‘permanent disability’ to him), but this was just an embarrassment. McMahon has been the bad guy forever, but by the end, the crowd were just sitting in uncomfortable silence: I actually felt sympathy for Vince, which was hardly the intended outcome. The only thing worse was the tag-team women’s match: even as a fan of women’s wrestling, this was an abomination which should have been struck from the record. The widow of Eddie Guerrero – middle-aged and having never “fought” until her husband died – got the winning pinfall.

At this point, the show had been undeniably disappointing. Fortunately, the final two matches basically saved the event. John Cena has been WWE’s most popular wrestler for what seems like ever – an eight-time world champion, coming in – but the crowd appears to have grown increasingly-tired of him. The monstrous Batista, whose neck has to be about the size of my waist, was the adversary, and was the reigning champion, the heat helped by having herniated a disc in Cena’s neck in 2008. What really helped this match was the crowd being into it on both sides, trading chants for both men, etc. In the previous contests, it had either been obvious who they supported, or they just didn’t care. Not so here, and that amped up the intensity significantly. Cena finally won: make that a nine-time world champion.

Finally, it was Undertaker vs. Shawn Michaels, a sequel to last year’s contest, almost universally acknowledged as the best match of the year. It was set up that the defeat led Michaels to become obsessed with beating the Undertaker, who was 17-0 in Wrestlemania events [yeah, when the results are predetermined, that’s not as impressive, but simply being capable of taking part in that many Wrestlemanias is a feat in itself], which destroyed his partnership with Triple-H, costing them the tag titles. Michaels eventually got his rematch, after making the Undertaker lose his heavyweight crown – but the stipulation was, if he lost, it would end his career, so it was that against the most-fabled streak in professional wrestling history.

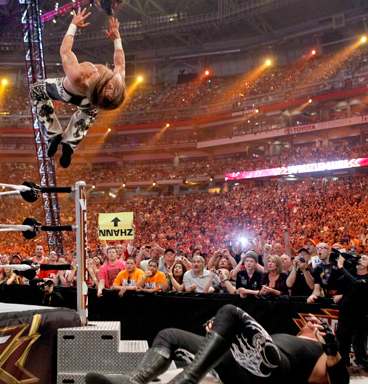

At last. The gap between bad art and good art has probably never been more starkly-demonstrated in my experience, as the final match lived up to all expectations and hype. Again, the crowd were a huge part of the experience, with dueling rhythms of “Un-der-ta-ker!” and “H-B-K!” [Michaels being known as the Heartbreak Kid] filling the cavernous space, as the two legends battled, back and forth. Even knowing the final result was predetermined didn’t matter: we avoid “spoilers”, preferring to be surprised, and genuinely had no idea of how this would turn out. The two men, both born before I was, threw everything they had at each other, up to and including a back-flip by Michaels off the top rope onto Undertaker as he lay prone outside the ring on the announcer’s table (left).

Right until the end, it seemed one man would prevail; then the other. Michaels just wouldn’t stay down, and the Undertaker seemed at a loss of what he could do to defeat his opponent. He seemed on the verge of showing mercy, but Michaels pulled himself up and slapped his opponent across the face, bringing him back. Undertaker delivered another Tombstone Piledriver – if you don’t know what that is, it’s what it sounds like – and that was it. The streak survived. Michaels’ career was over. However, the winner left the ring first, leaving it to Michaels, with both sets of fans now united in their vocal appreciation for what they had witnessed.

Of course, wrestlers have a habit of never “retiring”, and even if would devalue what happened in Phoenix on Sunday night, I’d not be surprised to see Michaels back in the ring eventually – as he said afterward, he’ll probably drive his kids nuts, after three weeks of him hanging around the house. But for now, it was an epic moment, one which almost redeemed the mediocre nature of what had gone before. We’re glad we went, and wouldn’t exchange the experience of that final match for anything. But next year… Even if it was in Arizona again (and it isn’t), we’d just buy the pay-per-view and stay at home with some friends and a few beers.