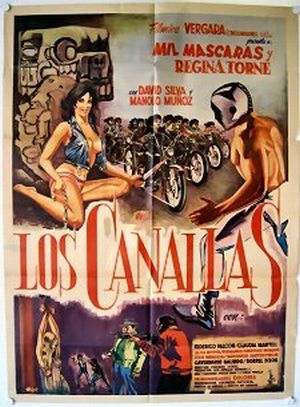

Incredibly Bad Film Show: Los Canallas

Dir: Federico Curiel

Star: Mil Mascaras, Regina Torné, Fernando Osés, Claudia Martell

a.k.a. Ángeles Infernales

Mexican wrestling movies are a different breed entirely. Sure, WWE wrestlers make movies, and to a large extent, the characters they play are simply an extension of their in-ring personae. John ‘Hustle, Loyalty, Respect’ Cena? Get him to play an ex-marine in…er, The Marine. Demonic hell-spawn Kane? Psychotic serial killer: See No Evil [though Glenn Jacobs, the man responsible, has a degree in English literature, is a former third-grade teacher, and supports Ron Paul] But the key difference is that none of these movies include any actual professional wrestling.

Contrast the Mexican versions, where Mil Mascaras (or Santo, Blue Demon, etc.) is a crime-fighter – but one whose day-job is as a wrestler, and that comes first. Everyone is comfortably at ease with this, both good and bad. For instance, the villains break their leader out of jail on Friday night because “everyone will be at the match.” And when they do, said leader takes on Mascaras in not one, but two wrestling matches. It’s as if, at the end of The Marine, Robert Patrick challenged Cena to a Falls Count Anywhere bout. The forces of good are just as wrestling obsessed. When they realize one of their number has apparently been kidnapped by the Infernal Angels, they don’t exactly rush to her aid, saying “Let’s wait until the first fall is over. Mil Mascaras will tell us what to do.” One fall later, he airily tells them, “I’ll be done soon, wait for me in the dressing room.” Like I said: wrestling first; rescuing your friend from torture and being slowly dipped into an acid-bath…later.

But I’m getting ahead of myself with the plot. Mil Mascaras flies in to land in his little private plane, on his way to take part in a wrestling show that afternoon. However, as he drives off, Cadena (Torné, who 24 years later, would be one of the leads in Like Water For Chocolate!) and her minion lob a smoke-bomb into his convertible. Rather than, oh, pull over, Mil makes an ill-advised attempt to continue driving which ends with him smashing into a wall a cut to the expensive automobile, completely undamaged, parked neatly on top of a pile of rubble beside a wall.

Turns out Mil was responsible for sending her boyfriend Rocco (Osés) to jail, and Cadena is implacably set on both breaking out her boy, and bringing Mascaras down. She has taken over the Infernal Angels, the gang Rocco ran, and she makes various attempts on the wrestling legend, such as trying to unmask him – only to be foiled, because Mascaras appears to have foreseen this eventuality and wears a second mask underneath the first. Brilliant! She has minions armed with a range of interesting devices for administering slow-acting poisons to her enemy, so he will lose or be easier to beat up. The idea of using something lethal instead, never seems to cross her mind.

Despite the drug-induced haze, Mascaras remembers Cadena’s ‘deep, cold voice full of hate,’ and that clues his friends in to the Infernal Angels being involved. Estrella (Martell) knows one of the gang members, and she agrees to go undercover, joining the Angels to find out what Cadena is up to. This involves a strange occult initiation rite (above), which resembles H.G. Lewis’s Egyptian feast, as re-imagined by Paul Verhoeven for Showgirls, albeit without the nudity (this being 1968). Estrella’s pal describes it as “cruel and difficult,” but that description applies mostly to the poor viewer who has to sit through this entirely inappropriate musical number. Mind you, Cadena also shakes her thang in the opening scene, for no apparent reason there either, and one wonders if this was some strange, Bollywood lucha co-production.

Cadena is successful in breaking Rocco and his cell-mate Hook – named because he has a hook in place of one hand – out of prison. She does so by giving them a transistor radio which a) functions as a walkie-talkie and contains something like thermite wire, which she activates remotely in order to burn through the prison bars. Really, this woman’s talents are sadly wasted, she should have been working for Q Branch. Like all good Mexican boys, he heads home to his mother, only to find her rather less than maternal. This might be because she’s just been visited by the police. Or the result of her realizing she’ll have to hand back the money Rocco gave her husband “for safekeeping.” Moral ambivalence at its finest.

I’ve reviewed some other lucha movies before, but this was the first one to reach the deliciously-loopy standards necessary for Incredibly Bad status. Perhaps the finest moment is when Mil has the chance to discover the Angels’ hideout. He declines the offer of help, saying “No, I’ll go alone to avoid suspicion.” This doesn’t work quite as well as hoped, since less than one minute later, minions are reporting to Cadena that Mil Mascaras is outside. There’s a very good reason for this, because the image below shows what his idea of “avoiding suspicion” involves walking up the front-door dressed as shown:

So, in addition to the ever-present mask, that’s a shiny gold shirt, powder blue pants with matching boots and a package which appears to suggest that Mil is very pleased to be fighting crime. It seems there is no word in Mexican for “undercover”. After another failed attempt by Cadena to seduce and poison him (using a ring apparently capable of containing the entire annual output of Hoffman La Roche), Mil escapes, though leaves a messy souvenir behind. If ever I become an evil overlord, I will instruct my underlings to check the contents of oil-barrels before machine-gunning them repeatedly, to ensure they contain my enemy and not one of their colleagues.

After 65 minutes with no mention of this whatsoever, it is revealed that Rocco is actually the Black Hood – another masked wrestler – who was apparently scheduled to fight Mascaras in the next show. Good job he broke out of prison then. Estrella tells Mil this, but rather than going to the police with this information about a notorious fugitive, he decides to play along, on the dubious assertion that “I’ll try to unmask him in the ring so he can be taken away by the authorities in front of an audience.” Yes, never mind the moral responsibility or safety issue – think of the ratings!

The first match ends in a no-contest, Mascaras being taken to the hospital after being snogged by one of Cadena’s minions wearing poisoned lipstick, and a “mask vs. hood” match is declared for the following week – the loser has to reveal his true identity. It’s during this contest that they realize Estrella’s is about to go for a really deep skin cleanse – but, as noted above, that can wait until Mascaras has won his match. Fortunately, there’s discord in the Angels, with Hook making a play for Cadena, and getting into a brawl with Rocco – a fight which, unfortunately, knocks a burning brand against the rope which is keeping Estrella out of the acid.

Naturally, Mascaras shows up just in time to save her, though I was disappointed no-one falls into the acid, which seems like a breach of B-movie etiquette rule #47: “He who sets the acid-bath, gets the acid-bath.” We’re left with Rocco’s mother bemoaning the fate of her son, and the final lines provide the moral to this masked fable: “Having a child represents a serious responsibility. Those that don’t meet it will suffer the consequences sooner or later.” Have to say, that’s probably not quite the final thought which will stick with me from this one.

B-