The Art of the Remake

It’s remake week here at Trash City, so as well as reviewing a few examples of the “genre”, figured I might as well put together a few philosophical notes on the topic. Remakes tend to come in for a lot of flak, but they are something of a double-edged sword. Some of my favorite films have been remakes, and you might be surprised to learn that highly-regarded movies as diverse as Dangerous Liaisons, The Maltese Falcon, Against All Odds, Fatal Attraction and A Fistful of Dollars, all fall into the category to some extent. It is a somewhat nebulous group: technically, every film version of Hamlet ever made is a “remake,” but we’ve got to draw the line somewhere – so if it’s in the public domain, it’s fair game.

That said, there do appear to be certain guidelines which influence the remakes that are successful, from those that are regarded as cinematic abominations. After the jump, here are some thoughts on these rules.

1. Remake movies where there is room for improvement.

“There is a willful, lemming-like persistence in remaking past successes time after time. They can’t make them as good as they are in our memories, but they go on doing them and each time it’s a disaster. Why don’t we remake some of our bad pictures – I’d love another shot at Roots of Heaven – and make them good?”

2. Bring something new to the party.

There’s no point in doing something that’s a slavish remake, otherwise, what’s the point? Sometimes, there is an aspect which was obviously missing from the original, for reasons that made sense at the time – in the original Cat People, the sexual tension had to be underplayed, even though it was obviously a major theme, because of the censorship climate. Paul Schrader took that aspect, turned it up to eleven and made it in your face. Same with David Cronenberg and the body-horror aspect of The Fly.

3. The times, they are a-changing…

It should be obligatory for every horror remake to include a scene in which a character waves a cellphone above his or her head, and mutters, “Dammit! No service!” To steal from another song, Fings Ain’t Wot They Used T’Be: so if you’re bringing your remake into the current day (as almost all do), you can’t pretend it’s still the seventies. People are now more connected than they were, and the ceaseless march of technology potentially affects not only horror movies but thrillers and even romantic comedies (You’ve Got Mail updated The Shop Around the Corner with email replacing letters). But some things just won’t translate. For some reason, this seems to affect movies based on remaking TV shows in particular: Wild Wild West, The Mod Squad and The Avengers all failed miserably to work in the present day, regardless of whether they retained the period setting or not.

4. Some things are sacred.

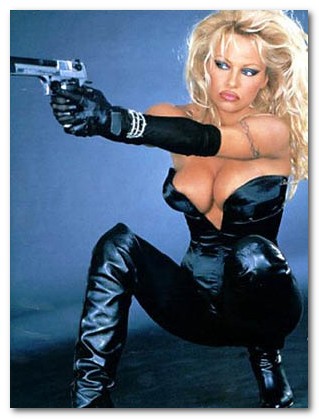

Even contemplating a remake of Casablanca should be grounds for flogging [unless, of course, you’re going to make it star Pamela Anderson and call it Barb Wire. In which case, go right ahead] As a general rule of thumb, if you want to remake movie X, you need first to have proven that you can make your own film as good as movie X. So, if Tim Burton wants to remake Planet of the Apes or Willy Wonka, that’s fine. When Scott Derrickson wants to remake The Day the Earth Stood Still, and his track record extends no higher than The Exorcism of Emily Rose… Not so much. Just because you can remake a classic, doesn’t mean you should.

5. The world is shrinking.

Stop with the foreign remakes. Sergio Leone could get away with producing knock-offs of Kurosawa movies, because just about no-one outside of Japan had seen them. Nowadays, thanks to an unholy combination of the Bays [and I mean E- and The Pirate, not Michael], any half-decent movie is available anywhere in the world, usually within a few days of release. Some genres are particularly on the ball here: anime and horror, for example. Do not expect fans to be enthusiastic about your remake of a film they have already seen and either a) know and love, or b) don’t think is very good to begin with. Gore Verbinski’s The Ring has a lot to answer for in this area: namely, the line of inferior J-horror knock-offs foisted upon the American public.

6. Show some respect for the original.

It won’t help your cause to have the creator of the movie on which you’re basing your work, sniping from the sidelines. Witness the spat between Abel Ferrara and Werner Herzog over the latter’s “reimagining” of Bad Lieutenant. Ferrara said “I wish these people die in Hell. I hope they’re all in the same streetcar, and it blows up,” and Herzog – a man who had some epic battles with Klaus Kinski, of course – replied “Wonderful, yes! Let him fight…I have no idea who Abel Ferrara is.” That kind of thing is likely to alienate the people who most liked the original, and they could be your core audience.

7. Why are you remaking this?

The reason behind the remake is probably the crux of the matter. There are times when it’s obviously little more than sheer laziness: there’s no need to bother coming up with a new story, when there’s a script here which already proved (more or less) successful before? So is this because you think you have something new you can add? Because the original had a great plot, but the FX of the time weren’t up to the necessary level? Because the old story now has a new resonance? Or because it’s a job, given to you by a studio intent on raping its back-catalogue of titles for a quick buck?

Like anything else – adaptations, sequels, etc. – remakes are a tool, and as such can be used for good or evil cinematically. Into which category the results fall probably depends more on the talents of those involved in the project than anything else. But knowing this won’t stop me from calling in an air-strike on Hollywood, if the mooted remake of Blade Runner ever comes to pass.