Kindle Surprise: Great Expectations, by Charles Dickens

“That was a memorable day to me, for it made great changes in me. But it is the same with any life. Imagine one selected day struck out of it, and think how different its course would have been. Pause you who read this, and think for a moment of the long chain of iron or gold, of thorns or flowers, that would never have bound you, but for the formation of the first link on one memorable day.”

I had some concerns going in, being aware that this story was originally published in installments, by the weekly publication All the Year Round. I had bumped against another similarly episodic work earlier in my Kindling, Alexandre Dumas’s The Three Musketeers, and I found it unreadable, to the extent that I bailed after only a few chapters. It was painfully clear that Dumas was being paid by the word, and this reduced the story to grinding on at a painful and tedious pace, with copious descriptions of the tiniest elements. I feared this might be the same, but hoped the fact that Dickens owned and operated All the Year Round, rather than being merely a contributor, would help avoid this falling into the same traps.

Should I describe the plot? Do I need to? Has the spoiler statute of limitations expired, considering the book came out over150 years ago? I mean, even our son – for whom, sadly, reading is something very low on his list of leisure pursuits, likely falling between household chores and dental treatment – remembered reading this at school, albeit after some initial confusion with the plot to Oliver Twist. However, I was entirely unfamiliar with it, having neither read the book, nor seen any of the adaptations (most notably David Lean’s one from 1946, starring John Mills), so the various twists and surprises were indeed surprising. On that basis, let’s assume everyone else is as ignorant as I am.

It’s an oddly asymmetric book. While there’s an obvious hero, or at least central character, in Pip, an orphan, there is no antagonist, unless you consider life itself as qualifying. He’s brought up by his older sister and her blacksmith husband, and the first half concerns his youth, encounters with an escaped convict and relationship to creepy (but right) recluse, Miss Havisham, and her foster daughter, Estella. However, his life is changed forever by an inheritance from a mystery benefactor, which allows Pip to escape the grinding poverty of smithy life, move to London and become a gentleman of leisure. However, he’s in for a nasty surprise when the true nature of his benefactor shows up on his doorstep one rainy night, kicking off a series of events that will leave Pip poorer but wiser – and possibly, happier as well.

Which I guess is the point: money can’t buy you happiness. But, boy, does Dickens take the long road to that moral, especially since it’s a destination of which I’m already aware. However, the journey is not an unpleasant one. Pip does seem like a bit of an asshole at times: soon as he gets his mysterious inheritance, he bails on those who raised him for the big city, without much of a second thought or look back. While part of that is due to the terms imposed by his benefactor, and to his credit, he does seem to feel a bit guilty, that doesn’t stopped him from living the life of the indolent rich. He’s more than happy to use his new-found wealth for the benefit of his housemate, so why not send some back to Joe and Biddy? Dick move, bro’.

Perhaps the most memorable character is Miss Havisham, an old maid who has become bitter and twisted after being jilted, sitting around her largely decrepit estates in the dress she should have worn on her wedding day. She bring up her foster daughter, Estella, as a beautiful demon, designed for the sole tasks of breaking men’s hearts as revenge. This was one aspect which felt as if it had been pulled from a Wilkie Collins’ mystery, though it may just be that Collins is the Victorian author with whom I’m most familiar, and so might share a similar popular style. That said, I’d like to read a novel detailing their story, probably more so than one focusing on Pip’s inner monologues. [Peter Carey’s Jack Maggs apparently does something similar, telling part of the story from the convict’s point of view.]

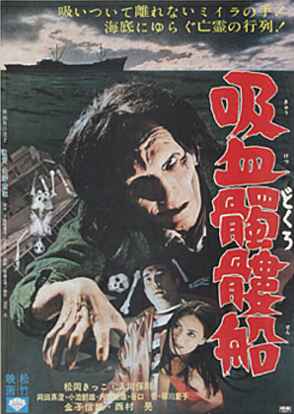

I was pleasantly surprised by the flashes of dry, Dickensian humour present. If it’s not exactly Douglas Adams, nor was this a particular chore to read, though some of the language was certainly archaic to a modern ear. However, it wasn’t exactly an unstoppable page turner either, and I typically found myself putting it down after a chapter, or at most, two. I am, however, curious to check out some of the film versions, and see how they compare. Not just the David Lean one, perhaps also 2011 BBC adaptation, with Ray Winstone as Magwitch and Gillian Anderson as Miss Havisham. Or even An Orphan’s Tragedy, a Hong Kong version starring… Bruce Lee as their take on the young hero. Now, watching Pip wield his nunchaku against Magwitch: that’s something I can get behind…

“Pip, dear old chap, life is made of ever so many partings welded together, as I may say, and one man’s a blacksmith, and one’s a whitesmith, and one’s a goldsmith, and one’s a coppersmith. Divisions among such must come, and must be met as they come.”