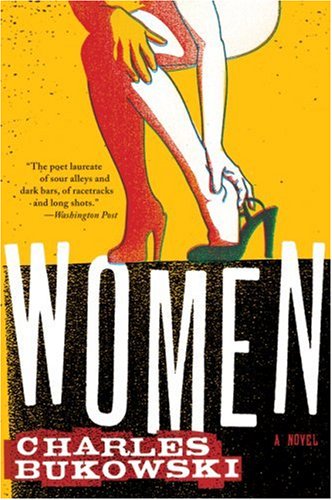

Kindle Surprise: Women, by Charles Bukowski

The rules: A couple of years ago, I wrote about my Kindle, and the torrent I downloaded of 1,425 e-books. Going forward, I will be writing about each book I read off it. The aim is to expose myself to titles I wouldn’t otherwise read, from all period of history, but with a certain discipline.

- I don’t get to choose the book. I’m going through them in the order they appear on the screen. This is vaguely alphabetical by author first name, but that depends on the tags applied to each file.

- I’m restricting myself to one book by each author.

- I am not permitted to skip a book.

- I must finish one book before beginning another, but can stop reading a book if I can write 500 words on why I will be stopping

- However, I am allowed to have a different book simultaneously on my phone.

“That’s the problem with drinking, I thought, as I poured myself a drink. If something bad happens you drink in an attempt to forget; if something good happens you drink in order to celebrate; and if nothing happens you drink to make something happen.”

Bukowski is someone I tend to confuse with Chuck Palahniuk for some reason, though I’m not sure they have a great deal in common beyond a first name and a tendency (somewhat) to write about the raw underbelly of society. My first encounter was cinematic: the Belgian film, Crazy Love, based on three of Bukowski’s tales, and depicting a man’s inability to find true love, resulting in a downward spiral ending in suicide. I think it’s a very good film, but it’s not exactly the kind of thing you’d slap on for entertainment.

Fast forward close to 30 years, and I encounter Bukowski again, this time in his home environment of the written word. My instinct is this is less fiction, than thinly-disguised autobiography, with the story depicting a slice of life for “Henry Chinaski,” a writer who has achieved some popular success late in life. This has allowed him to abandon his day job at the post-office, and live on the income from poetry readings, royalties, etc. His life outside of this consists mostly of heavy drinking, and dysfunctional relationships with a series of women, who range from relatively normal, through to borderline psychotic [One wonders how the women felt about their portrayal]. Concepts such as monogamy seem entirely unknown to Chinaski, who will seize any opportunity he can for a fuck. He doesn’t appear to care much about the emotional toll this takes on those in the relationship, and in terms of a character arc, there isn’t much to speak of. At the end, however, he does hang up on another in the long line of literary groupies (reading rats? Is there a name for them), which I guess counts as some kind of progress.

What salvages the character – and the book – is the ferocious honesty. The author and/or his character are under absolutely no illusions about what a bastard they’re being. The overall tone reminded my of Klaus Kinski’s autobiography, All You Need is Love in a number of ways. That’s not just the obsessive sexual compulsions, but also the cheerful willingness to not care about whoring themselves out. “That night I gave another bad reading. I didn’t care. They didn’t care. If John Cage could get one thousand dollars for eating an apple, I’d accept $500 plus air fare for being a lemon.” Mind you, I also have to confess a sneaking admiration for the “hero” here, who finally got to quit his day job at the age of 49 – a mark I’ll reach myself in April – and seized with both hands, the opportunities that life presented him as a result. But, man: I clearly missed my chance if, as this book implies, all you had to do was write poetry and you’d have random chicks calling you up to pop round for a few drinks and multiple aardvarking. Of course, this was written in 1975-77 – a very different era, before sex could kill you.

I must say, it does get more than somewhat repetitive by the end, even broken up into 100+ chapters, some only a couple of pages long. While the spectrum of women in his life does show variety, it seems more in the physical sense, and none of them stick around long enough to make much impact, either on the reader or Chinaski. But the moral appears to be, why worry about bothering to treat someone with respect, even for the purely selfish reason that they’ll stick around – after all, there will be another one along in a minute? It’s a difficult mindset to relate to, though I will confess to wondering what the film version might have been like. The rights were sold to Paul Verhoeven at one point, and I can’t think of any other director who possibly – just possibly – could have done the mean spirit here justice.

‘I’m not a thinker. Every woman is different. Basically they seem to be a combination of the best and the worst – both magic and terrible. I’m glad that they exist, however.”