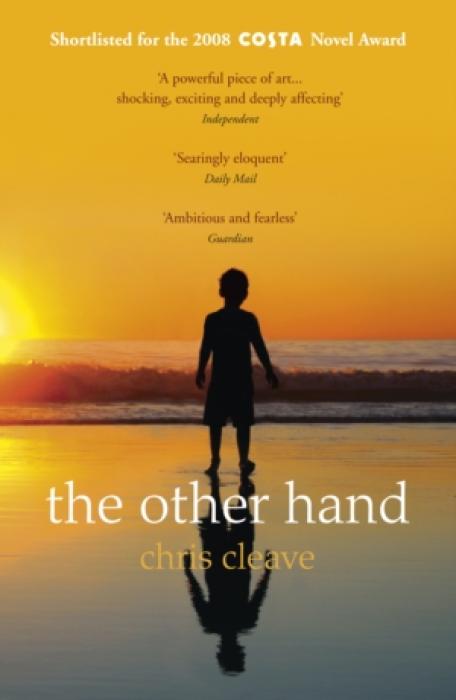

Kindle Surprise: Little Bee, by Chris Cleave

a.k.a. The Other Hand

“We must see all scars as beauty. Okay? This will be our secret. Because take it from me, a scar does not form on the dying. A scar means, ‘I survived’.”

Another book that falls into the category of “ones I’d never had read without this project,” it turns out to be a worthwhile endeavour. By coincidence, it’s a story told, like the last book I covered, Cold Mountain., in chapters that alternate between two very different viewpoints. That is really about the only similarity though: while Cold was very much a period piece, this is perhaps even more relevant now – the weekend of the Paris terrorist attacks – than it was when it came out in 2008. It tells the story of “Little Bee,” a Nigerian refugee, who flees a hellish civil conflict in her home land to England, and is then held in an immigration detention center for two years. When let out through a bureaucratic bungle, she makes her way to the home of the only people she knows, the O’Rourke’s, a couple she met on a Nigerian beach under disturbing (and initially vague) circumstances. The other half of the narrative is Sarah O’Rourke, a magazine editor, devoted mother and not-so-devoted wife, who is understandably surprised to see an escaped refugee show up on her suburban doorstep.

Cleave worked in one of the detention centers for a while, and wanted to write the book to humanize refugees, by picking out one of the myriad of stories present. On that basis, he succeeds, with Little Bee certainly a sympathetic character. She’s smart, despite her lack of education, teaching herself English during her incarceration, and independent, making her way from the center, through London, to the only address she knows. She even has a dry, self-effacing wit. It’s just like an illegal immigrant version of Finding Nemo! [Okay, that’s a stretch] Sarah is… considerably less so, coming over to a certain extent – particularly early – as the kind of whiny media luvvy deserving of mockery. That becomes muted later on, when the facts of her first encounter with Little Bee become apparent, and what that cost Sarah, both physically and personally – you can certainly argue that the price she paid, included her husband, is almost as much as that of Little Bee.

You do gain an insight into, and appreciation for, the plight of the “true” refugee, and the author is also to be commended for laying off any obvious political message. While it’s clear he’s saying we need to be more tolerant of, and treat better, those who come to our country seeking sanctuary, he avoid doing so through “soapbox writing,” and largely lets that come through the actions and thought of his two main characters. However, it all seemed more than a little contrived towards that end, in terms of both those he portrays, and the events that happen to them. I sincerely doubt Bee’s story is even slightly typical of most asylum-seekers, and that makes it relatively easy to dismiss as unrepresentative. As usual, the truth is not to be found at either extreme; neither Bee’s near-saintly acts, nor in the “benefit scrounging scum” beloved by certain tabloids. Though it would have been more of a challenge, and more impressive achievement if successful, to have taken one of the latter and turned them into a hero or heroine.

I’m not certain of the reason for the difference in title: in the US and Canada, it’s called Little Bee, while the original one was The Other Hand. While it was the former version I read, and so have used as the main title throughout this piece, I must say, the latter probably makes a good deal more sense, having a double meaning, one of whose aspects is reflected in elements of Sarah’s story. I can’t say it has necessarily changed my view on the thorny topics of immigration [it’s a nightmare trying to come up with any kind of regulatory system – something undeniably necessary – that can cope fairly and justly with the vastly differing circumstances thrown at it], but the book did still give me food for thought, without ramming its opinion down my throat.

“Horror in your country is something you take a dose of to remind yourself that you are not suffering from it.”