In Praise of Narwhals

I don’t normally hold much common ground with the ‘Intelligent Design’ crowd, but even I have to admit that evolution is hard-pushed to explain the existence of the narwhal – to me, it seems not just proof of the existence of god, but that he/she possesses a twisted sense of humour. It’s the kind of animal that could only have been invented at the tail-end of a long college party, when it seemed like a good idea to outfit a marine mammal with a corkscrew on its nose. Narwhals should consider themselves fortunate that their creator apparently fell asleep, before deciding to add a can-opener and a pair of scissors to their other end.

While initially merely amused by narwhals, the more I learned, the more I realized that they fall into the category of “unjustly overlooked.” Dolphins get all the cetacean press, but all they really have to offer is a smile like Lindsay Lohan leaving court after a ‘not guilty’ verdict. Narwhals are much, much cooler, truly equipped to be the ultimate party animals (far surpassing dolphins, and their bottle-noses). That horn can be over nine feet in length., and when Queen Elizabeth I was presented with one in 1588, by privateer Martin Frobisher, she placed on it a value of ten times the horn’s weight in gold. Suck on that, Flipper.

Actually, it’s not a ‘horn’ as such, but a tooth that grows through a hole in the narwhal’s upper lip. The narwhal has two; almost always, it’s the left-hand one that expands out, but occasionally, the right tooth won’t get that message, leading to a rare, bi-pronged narwhal. The British Museum reportedly has one – no word on whether this leads to some kind of tusk envy among others of its pod. [Hence the saying, “As happy as a narwhal with two horns.”] The actual purpose of it remains a mystery, which is part of the animal’s appeal: obvious uses like fighting or punching holes through the Arctic ice, just don’t seem to happen.

However, in 2005, scientists from Harvard and the National Institute of Standards and Technology took a look at it through an electron microscope. They discovered 10 million nerve endings going from the core outward, and believe the horn is basically a massive sensory organ, that can detect changes in temperature, pressure, etc. It’s almost like the tooth is built in reverse, with the nerves on the outside, causing The New York Times to call the appendage, “one of the planet’s most remarkable.” When the whales break the surface, waving their horns around, it may be the equivalent of us licking a finger to tell which way the wind’s blowing, to help predict the weather.

Really, not much of a “Mystery” Whale, is it?

The name translates from Old Norse as “corpse-like whale,” describing the whale’s mottled black and white skin – those Old Norsemen were clearly not exactly observant, apparently managing, when naming the beast, to miss that whole F-sized tusk thing. The Inuits got it right, calling the narwhal Qilalugaq qernartaq – no, I didn’t just fall asleep on the keyboard – which translates to mean, “the one that points to the sky.” It’s generally thought that narwhals are involved in the unicorn myth. This is somewhat hard to swallow: I mean, if I was cruising the arctic seas and saw one, my first thought would hardly be, “Look! A horse with a horn on its head. We need a virgin to catch it.” However, these were the same sailors who apparently confused manatees with Darryl Hannah, when Rosie O’Donnell would have made more sense. So I suppose anything is possible.

One thing is certain. Narwhals combine style and function, mystery and grace, intelligence and strength, in a way that lesser species would kill for. They may, arguably, be quite the coolest animals on the planet.

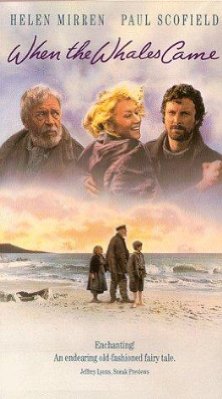

When the Whales Came

Dir: Clive Rees

Star: Max Rennie, Helen Pearce, Paul Scofield, Helen Mirren

Narwhal fans are not exactly well-served by the cinema. As in most of culture, it’s damn dolphins that get all the coverage, going back to the 1916 silent film, The Fate of the Dolphin. Since then, we’ve had Flipper, Day of the Dolphin and even Touched by a Bleedin’ Dolphin. In contrast, the most well-known cinematic moment for the poor narwhals, is a ten-second cameo in Elf. But this 1989 film, while less renowned, contains significantlyl more tusky goodness – though it takes its time getting there. We were drawn in by a two-line synopsis that mentioned two of our favourite things: narwhals, and mobs of villagers. However, that really only occupies a small part of the film, albeit the climactic moments.

It’s set around World War I on the Scilly Isles, off the coast of Cornwall, on an island where the inhabitants largely survive by scavenging from whatever the sea throws up on the beach. Two children, Daniel and Gracie (Rennie and Pearce), befriend a reclusive old man (Scofield), whom the rest of the local treat with a mix of fear, suspicion and derision, because of his trips to the cursed, now-deserted nearby islet of Samson. He’s known as “The Birdman”, because he carves exquisite birds out of driftwood. That’s what attracts Daniel, who wants to learn the art partly as an escape valve from his abusive father. Gracie has no father at all, since he went off to join the navy, so she’s being brought up by her struggling mother (Mirren).

An ill-fated fishing expedition by the kids lands them on Samson, where they find a narwhal tusk over the fireplace in one of the abandoned houses. Back on their own land, they find some locals suspect the Birdman of being a German spy, because of the beacon fires he sets, and set out to make him pay. However, he is more pre-occupied with a narwhal which has beached itself on the shore, and tells Gracie and Daniel it must be returned to the sea, before it brings the rest of its pod ashore behind it – an act that would bring doom to this island, as it did to Samson. Which is where the mob of villagers comes in…

In the interests of accuracy, it should be noted that, I believe, narwhals are very rarely stranded on the British coast [only four instances have been recorded since the days of Good Queen Bess], so the concept here is probably, ah, on thin ice, zoologically-speaking. Though the massacre of narwhals in large numbers, sadly, still goes on: late last year, up in Canada, at least 600 were killed by locals after getting hemmed in by ice. I’d be more inclined to take claims of this being a native tradition seriously, if snowmobiles and semi-automatic weapons weren’t apparently involved, and the media kept away. Happy to use the tools of modern civilization; not so willing to leave your questionable “harvests” behind, or face public opinion when the world sees what’s going on.

Back to the film. It’s an idea that works very nicely, both as a metaphor for the war – we note the prominence given to a narwhalesque spiked German helmet in the local school – and as a reverential acknowledgment that narwhals have a mystical quality, perhaps more so than any other aquatic mammal. The movie is certainly helped by a strong performance from Scofield, and very natural ones by the two children, against a marvelously scenic backdrop. The pace is relaxed, to say the least – those, like us, lured in with the promise of narwhals, will likely find themselves looking at their watches. But as an unhurried, Sunday morning kind of a film, it certainly has some charm.

B-