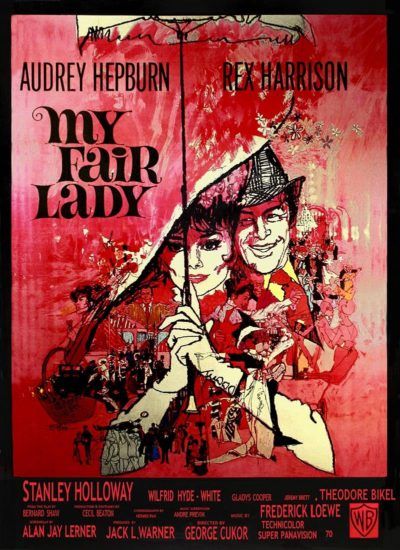

Rating: A+

Dir: George Cukor

Star: Rex Harrison, Audrey Hepburn, Stanley Holloway, Wilfrid Hyde-White

London (Dec 5). In the latest case of harassment to become public, The Grauniad has learned of allegations of abuse made against Professor Henry Higgins, a speech therapist working out of his home in Wimpole Street. The claims were made by former student Eliza Doolittle, who stated that she was the target of threats by Higgins. According to the victim, she was told that if she refused to comply with his demands, she would have to “sleep in the kitchen amongst the black beetles and be walloped by Mrs. Pearce [another employee at the facility] with a broomstick.” Higgins allegedly showered her with abusive terms, including “draggle-tailed guttersnipe” and “barbarous wretch”, while also engaging in slut-shaming, referring to Ms. Doolittle as an “impudent hussy.”

Doolittle, describing the Professor as “a great bully,” says she was traumatized by the experience, which have left her a completely changed woman, and currently unable to resume her former employment as an independent horticultural sales advisor. She says she is now recovering from Stockholm Syndrome, but still suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder, describing nightmares in which Higgins is shot by a firing-squad. Her claims appear corroborated by a colleague of the Professor, Colonel Pickering. He says Higgins at one point asked him, “Why can’t a woman be more like a man?” and frequently expressed misogynistic views, describing woman as “exasperating, irritating, vacillating, calculating, agitating, maddening and infuriating hags.”

Reached for comment, Professor Higgins responded with a statement regarding the allegations: “The great secret is not a question of good manners, or bad manners, or any particular sort of manner, but having the same manner for all human souls. The question is not whether I treated Ms. Doolitle rudely, but whether she ever heard me treat anyone else better.” However, documents indicate Higgins had previously reached an out-of-court settlement with Doolittle’s family, paying a significant cash sum following a private meeting with her father.

Of course, in the less enlightened times of the sixties, this sordid material was fodder for a lighthearted Broadway musical comedy. Somewhat prescient to note Emma Thompson’s comments, made back in August 2010 when she was working on the script of a remake. “It’s a very terrible thing [Alfred Doolittle] does, selling his daughter into sexual slavery for a fiver… This is a very serious story about the usage of women at a particular time in our history. And it’s still going on today. Yes, OK, it’s a wonderful musical, but let’s also look at what it’s really saying about the world.” With that attitude, I’m not at all surprised the remake was shelved. I wouldn’t rush to see a feminist diatribe remix, put it that way.

And that’s not even going into Thompson’s venomous hatchet-job on the late Hepburn. “I’m not hugely fond of the film. I find Audrey Hepburn fantastically twee… She can’t sing and she can’t really act, I’m afraid.” Let’s pause briefly, to consider the irony of the word “twee” as criticism, from a woman many will know best from her portrayal of a limp Mary Poppins knock-off. Though I will confess, as far as singing goes, Thompson has a point. While Hepburn can carry a tune, as the Oscar-winning Moon River shows, she is not the soprano for whom the part of Eliza Doolittle was written by Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe. Mary Martin was originally the target for the role, but when she turned it down, the stage role went to Julie Andrews.

However, at the time of the film, Andrews was still largely unknown outside the theatrical world. After Warner Brothers paid the then-enormous sum of $5 million for the rights (the equivalent of almost $40 million in 2017 money), they needed a bankable star – even one without the necessary range. Though Marni Nixon did not receive a credit as the singing voice, it wasn’t particularly a secret then, and I’m perfectly fine with it – even if you can spot every precise moment where the Nixon kicks in. To me, it’s not much different from having a stunt double, who does the things an actress can’t. You can fake singing, a great deal easier than you can fake acting, and while I’m sure Andrews would have been perfectly fine, I can’t say I miss her at all here.

This is likely Hepburn’s best role of her career, exhibiting a steely resolve as the character transforms from that “draggle-tailed guttersnipe” into a swan. [Yet, preserving one of the points of George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion, it’s not birth or upbringing which makes Eliza a lady, it’s being given the opportunity and taking it.] We should also compare and contrast Hepburn’s credible Cockney accent with Dick Van Dyke’s in Mary Poppins that same year, opposite Andrews. Worth noting: Hepburn grew up almost exclusively on the Continent, with English just one of the six languages she spoke. #Impressed

It needs to be a great performance, to stand up against the blistering supernova which is Rex Harrison’s portrayal of Professor Higgins. It’s no exaggeration to call it my favorite performance by an actor of all time. There may be “better”, in the sense of creating a fully believable character, yet there’s not one I would rather watch. Indeed, I can’t think of another 170-minute movie which feels shorter: there’s hardly a scene which isn’t pure, unadulterated joy to experience. About the only exception is the creepy stalking of Eliza by Freddy Eynsford-Hill (Jeremy Brett), which has aged badly. I mean, “I want to drink in the street where she lives”? Really? Yeah, you make us want to drink too, Freddy.

Though he does play his part in arguably the film’s greatest sequence, at the Ascot races. I’m hardly a fashionista, yet can only marvel at the bedazzling selection of costumes by Cecil Beaton, likely numbering in the hundreds. Hell, I could spend the entire time simply looking at the hats, and few films in the Technicolor era have ever made such wonderful use of black and white. Though his reactions remain crucial, it’s a rare occasion where Harrison takes a back seat, letting Hepburn command the screen. The results are a glorious escalation, and virtually the last we see of the original Doolittle, as she exhorts a race-horse to “Move yer bloomin’ arse!” Fainting among the genteel crowd ensues. It’s as near perfect as a movie scene can be.

A thousand words in, and I haven’t even got to the songs. I’m a traditionalist with regard to musicals: if you can’t hum the tunes, I’m not interested. This is not a problem here. I am still whistling selections from it, several days later. I would be prepared to stack the songs here, head-to-head, and have it go up against any other musical in film or stage history. Few would be able to compete, I’d say. The numbers both propel the plot and accentuate the emotional depth: if you aren’t struck firmly in the feels when Higgins confesses, “I’ve grown accustomed to her face,” you may be a replicant.

This makes an important point about relationships: they’re not about changing the other person to suit your needs. It’s about accepting the other person for who they are, warts and all. At the end, neither Higgins nor Doolittle have intrinsically changed: the latter has been redecorated, that’s all. Yet, for (or, perhaps, as a result of) all their butting of heads, they’ve reached that point of acceptance and are together, as the Professor says, “For the fun of it.” Despite the apparent ambivalence of its ending, it’s actually one of the warmest, with everyone (save Freddy, but who cares?) in a better place. Happier ever after, indeed.

[December 2010] Damn, this is good. Harrison is completely majestic as speech researcher Professor Henry Higgins, who takes on Covent Garden flower-girl Eliza Doolittle (Hepburn), as the result of a bet, vowing to pass the “draggletailed guttersnipe” off at an Embassy ball. Initially, she is simply the tool to an end, but by the end, the fiery academic who had bemoaned, “Why can’t a woman be more like a man?” has now “grown accustomed to her face.” Hepburn and Harrison strike magnificent sparks off each other, the former eventually proving more than a match for the initial intellectual superiority of the latter. For a Hollywood musical, it’s surprising how much was of the original social satire remains, as intended by George Bernard Shaw when he wrote Pygmalion, the play on which the musical and film was based, in 1912.

[December 2010] Damn, this is good. Harrison is completely majestic as speech researcher Professor Henry Higgins, who takes on Covent Garden flower-girl Eliza Doolittle (Hepburn), as the result of a bet, vowing to pass the “draggletailed guttersnipe” off at an Embassy ball. Initially, she is simply the tool to an end, but by the end, the fiery academic who had bemoaned, “Why can’t a woman be more like a man?” has now “grown accustomed to her face.” Hepburn and Harrison strike magnificent sparks off each other, the former eventually proving more than a match for the initial intellectual superiority of the latter. For a Hollywood musical, it’s surprising how much was of the original social satire remains, as intended by George Bernard Shaw when he wrote Pygmalion, the play on which the musical and film was based, in 1912.

The rigid class structure of the time come in for particular lampooning, most notably at the Ascot races, though the ending of Shaw’s play was significantly changed to soften the final relationship. It’s perfectly fine by me, given the alternative is Freddy Eynsford-Hill (Brett), who comes off as creepily clingy, to the point of being stalkerish (“I spend most of my nights here. It’s the only place where I’m happy…”) That’s likely the film’s only weak spot. The songs, by Lerner and Loewe, are great, immensely hummable and catchy, even though none of the leading characters actually sing: Hepburn and Brett were both dubbed, while Harrison – and to a lesser extent, Holloway – don’t even bother to try.

Hepburn won the role over Julie Andrews, who’d played Doolittle on Broadway, simply through being better known – and notched only the second-ever million-dollar salary for an actress. While it’s easy to tell Hepburn was dubbed, it’s hard to imagine Andrews being as perfect as Hepburn is, in what’s effectively two roles. It’s a perfect romantic comedy for those who don’t like romance, because that angle is underplayed in favour of smart dialogue and fabulous characters, even for minor roles like Higgins’ mother. I doubt Emma Thompson’s upcoming remake (which has already seen Thompson diss Hepburn as “can’t sing and she can’t really act”) will be able to come within the same solar-system in terms of lasting appeal.